1. Introduction

1So far, there are above all reasons to assume a substantial degree of unfamiliarity of the sixteenth-century Antwerp market with the concept of a limited partnership, i.e. a partnership consisting of jointly and severally liable partners, on the one hand, and one or more silent partners, whose liability towards third parties cannot exceed the size of their initial investment in the company, on the other hand.2 First of all, only two examples of Antwerp partnership agreements establishing a limited partnership have been discovered thus far.3 Secondly, the fourth and last municipal attempt to record all Antwerp customs, the so-called Consuetudinescompilatae (1608), which provided for quite an elaborate title on private partnerships (title 4.9), did not incorporate a separate clause on the limited partnership as a distinct type of commercial company.4 On the other hand, the two examples do give proof of the fact that the limited partnership was not entirely strange to sixteenth-century Antwerp merchants.5 Therefore, this article examines the real degree of familiarity of the Antwerp market with limited partnerships in the long sixteenth century (1480-1620).

2An examination of such acquaintance is appropriate and desirable for two main reasons. First of all, it has been generally assumed that the idea of liability limitation and the appearance of limited partnerships constituted substantial factors and features in late medieval and early modern economic development for it provided a relatively safe way to attract and activate a large amount of money that had remained passively present in contemporaneous communities thus far.6 Likewise, it also allowed for the injection of financial means belonging to social groups that were presumed to refrain from economic affairs because of their social status. By means of limited partnerships, clerics, noblemen and officials could now participate in commerce anonymously as silent partners, since in principle their names were to remain excluded from the firma or name of the company. Likewise, they could fructify their idle capital without risking a loss of rank.7 Precisely because of this stimulating role, generally attributed to limited partnerships, it is surprising that, at first sight, such limited partnerships are hard to identify within the framework of the Antwerp market during the sixteenth century, in particular since at that time the city experienced its Golden Age. Therefore, a closer examination of the city’s familiarity with liability limitation becomes desirable in order to assess the latter’s role within the overall growth of the Antwerp market. A second reason that incites such assessment is framed within a legal context. So far, sixteenth-century Antwerp has been appraised repeatedly for the development of various financial innovations, more specifically with regard to the negotiability and transferability of financial instruments. A similar pioneering role has been attributed to the city with regard to the further distribution of the idea of limited liability over Northern Europe, and the city of Amsterdam in particular.8 Again, the exceptionality of limited partnerships discovered so far might refute this assumption and further support the belief of those economic historians stressing the independent development of the idea of limited liability in Amsterdam on the legal foundations of the so-called partenrederijen.9 So, in addition to economic historians, a profound examination of the familiarity of Antwerp-based merchants with limited partnerships will serve their legal counterparts as well.

3In order to assess the acquaintance of Antwerp-based entrepreneurs with limited partnerships, the most self-evident approach consists of a systematic analysis of all preserved partnership agreements by means of which a commercial or industrial company had been founded during the period under investigation. As regards the long sixteenth century, I could identify 141 – chiefly notarized – partnership agreements.10 However, as far as the categorization of private partnerships and the identification of limited partnerships are concerned, the respective partnership agreements present us with two significant impediments. Firstly, Antwerp notaries did not distinguish terminologically between various types of partnerships. Every kind of private partnership, whether it was a general partnership or a limited one, was called a compaignie, societeyt, or geselschap, irrespective of the presence of fundamentally distinguishing features.11 Secondly, early modern contracting parties were primarily concerned about internal relationships instead of external liabilities. Only seven partnership agreements contained clauses addressing external liability issues explicitly, of which only two contracts postulated the limited liability of one or more of its partners.12

4As a result, it remains utterly difficult to qualify and categorize the 141 partnership structures of the research sample by means of the external-liability-criterion. Therefore, the present article will scrutinize the applicability of various other distinctive criteria - beside the presence of explicit clauses on the limited liability of silent partners in the partnership agreements - in order to justly qualify a specific partnership as a limited partnership, and distinguish it from a general partnership. Such assessment will start from those two examples of limited partnerships known to us thus far, i.e. the Schetz-Pruynen-van Hilst Company of 1552 and the Balbi-Maggioli Company of 1604.

2. Contractual clauses on limited liability in early modern Antwerp

5In order to decide on the usability of extra criteria that allow for a distinction between general and silent partners, and consequently help to identify limited partnerships, a suitable starting point is provided by those partnership agreements which created partnerships that can be unquestionably labelled as limited partnerships for the reason that these agreements explicitly limited the external liability of one or more of their constituting partners.13 These contracts inform us about extra features that were common among silent partners in early modern Antwerp and distinguished them from their jointly and severally liable counterparts. In this respect, the absence of a silent partner’s name in the firma or name of the company as well as his abstinence from all trading and managerial activities proved to be significantly useful.

6The first (well-known) example of an Antwerp partnership agreement containing a clause, by means of which the external liability of one or more constituting partners was limited to the initial contribution to the partnership’s nominal capital, was recorded on the 1st of December 1552. The partnership, that was to begin its activities on the 1st of January 1553, united the (in)famous Schetz brothers (Gaspar, Melchior and Balthasar) with their Antwerp factor, Christoffel Pruynen, as well as their Leipzig factor, Adriaan van Hilst.14 The company was initially established for a fixed duration of six years and was to conduct trading activities between the cities of Leipzig and Antwerp.15 It was agreed that Christoffel Pruynen would administer the corporate activities in Antwerp, while Adriaan van Hilst was entrusted with a similar task in Leipzig. The individual capacity to act of both gouvernadores remained limited to some extent. Long-term contracts and purchases ‘of greater importance’ could only be engaged in with the consent of the other managing partner. This is obvious, if one takes into account that Pruynen and van Hilst could either jointly or individually obligate each other towards third parties. The role of the three Schetz brothers within the partnership was a merely passive one and was limited to a financial contribution of £4.000, equalling four ninths of the overall company. Pruynen contributed £3.000 and van Hilst £2.000.16 Still, the partnership agreement did not postulate the complete abstinence of the Schetz brothers from all corporate activities. Despite the fact that they were not expected to participate actively in the company’s activities, they were still allowed to interfere ‘as soon as they considered such intervention desirable’. The Schetz brothers were also granted the right to enter the offices of the company in Antwerp in order to check the account books, ‘like full partners are allowed to do’ and ‘as if their names had been mentioned in the firma as well’. Furthermore, Pruynen and van Hilst were not allowed to employ factors without the advice and consent of the three Schetz brothers. As a result, the actual involvement of the Schetz brothers remained limited to an internal and advisory level. It did not comprise external contracting, managerial or administering activities. Therefore, they saw their liability, contractually and explicitly, limited to the amount of their initial investment:

7‘ende ondersproecken dat dese twee administranten van deser compaingia Pruenen oft Hilst oft yemants vander compaingia weghen by heur geauctoriseert synde den handel deser societeyt niet hooger en sal moghen oft konnen beswaren tot des Gaspar Schets ende ghebroeders last dan tot vermoghen des camdaels boven gemencioneert in sulcker vueghen dat inghevalle van verachteringhe oft verlies (daer godt voorsien moet) die voors. Gaspar Schets ende ghebroeders des niet voorder en sullen belast wordden oft moghen verliesen, dat dat camdael van huerder syden in deser handelinge oft societeyt ghefourneert synde’.17

8Subsequently, the contracting parties explicitly declined all customs and laws that could have prescribed the joint and several liability of partners. In addition, the agreement reveals that it was of absolute importance that the names of the three Schetz brothers did not appear in the name of the company or firma. Both in Leipzig as well as in Antwerp, the managing partners, Pruynen and van Hilst, were to conduct business while using their both names exclusively, yet jointly.

9Thus, two distinctive features of the silent partners have become apparent: the absence of their names in the firma, and their abstention from all genuine partnership operations. A similar observation can be made on the basis of the limited partnership established in Antwerp in 1604 by the Genoese merchants Gio Francesco, Bartholomeo and Jeronimo Balbi on the one hand and Lorenzo Maggioli on the other hand.18 Again, the composition of the firma is decisive in distinguishing between general and silent partners, and the latter refrained from every kind of active involvement in the execution of the business activities. In the contract, it was agreed that Lorenzo Maggioli would execute the partnerships’ business in Antwerp as a general partner, whereas the Balbis - as silent partners - would stay in Genoa and limit their contribution to the company to the supply of 60.000 guilders. Maggioli, on his part, was to invest 20.000 guilders. Like in the previous example, the external liability of the silent partners had been explicitly limited to their initial investment: ‘... dettiBalbi non possinoessereobligati in modoalcuno a maggiorsommache a sudettefiorinisessantemilliachepongono per loroparticipatione’.19 In order to guarantee such privileged status of the Balbi brothers, Lorenzo Maggioli was not allowed to use their names while contracting with third parties. On the contrary, Maggioli promised to execute the company’s business ‘in his own name’.20

10So, in both examples the silent partners at hand possess two extra features that distinguish them from their jointly and severally liable colleagues, namely the absence of their names in the firma and their abstention from actively administering external business activities.21 Taking into account these features, it becomes possible to identify more limited partnerships among those partnership agreements that do not contain an explicit clause on the privileged status of one of their partners.

3. The firma-criterion

11On the basis of both characterizing features of silent partners, delivered to us in the aforementioned explicit examples of limited partnerships established in Antwerp, three other partnership agreements can be safely typified as contracts establishing a limited partnership.22

12In 1558, the Antwerp merchants Jan Gamell and Paul van Houte established a private partnership that essentially resembled an ordinary investment company.23 The parties contributed £100 each in order to finance their enterprise. Successively, the company lent £100 to Peter Sobrecht, a German merchant, at an interest rate of twelve per cent. Subsequently, the van Houte-Gamell Company created a private partnership with Peter Sobrecht, whereby both contracting parties, i.e. the van Houte-Gamell Company on the one hand and Peter Sobrecht on the other hand, invested £100 each. The total amount of £200 was to be employed, by Sobrecht and van Houte, in the trade of textile with Spain, and Jan Gamell was exempted from all daily business activities. In addition, the partnership agreement explicitly stated that Paul van Houte ‘was not allowed to use the name of Jan Gamell in any way whatsoever’. Consequently, one may conclude that Jan Gamell may be rightly considered as a silent partner, whose external liability was limited to his initial investment of £100.

13A second example dates from the year 1586. On the 18th of January, Gabriel de Hazu and Dirk Verhoeven established a sugar trade company for four years. Both contracting parties invested £1.000 each, either in cash or in goods.24 It was agreed upon that Dirk Verhoeven would administer and execute the business activities ‘all by himself’ and ‘in his own name exclusively’, while Gabriel de Hazu was principally exempted from all corporate activities, ‘unless he considered an intervention to be desirable’. Moreover, the contract stated that Dirk Verhoeven was not allowed to bind Gabriel to third parties or assign him as a guarantor for certain obligations. As a result, Gabriel’s risk never exceeded the £1.000 that he initially invested in the company.

14Thirdly, there is the textile trading company established in 1596 by Jean vande Vekene, widower of Jeanne de la Porte, and the four children (Marie, Suzanne, Anne and Elias) of the latter with her former husband, Nicolas Fruict.25 All the children were still under-aged, but Marie, aged 19, was already capable to participate actively in the trading business. Suzanne, Anne and Elias evidently refrained from all corporate activities. The partnership agreement was concluded for a fixed duration of three years and it was decided that the name of the company would sound like JehanvandeVekene, Marie Fruictetcompaignie. Again, one may conclude that Suzanne, Anne and Elias were merely silent partners in the partnership.

4. The abstention-criterion

15Unfortunately, as opposed to late medieval Italian and sixteenth-century Castilian partnership agreements, those recorded in Antwerp hardly incorporated a clause on the composition of the company’s firma.26 Accordingly, the application of the firma-criterion brought about only limited results. This modest result is compensated by the use of a second criterion, i.e. the idea that a silent partner, as a general rule, had to remain a passive partner as well, and thus, was expected to refrain from each kind of active involvement in the company’s daily activities. This criterion is admittedly applicable to the Antwerp research group for various reasons. First of all, the criterion was generally accepted in foreign practice as well, more specifically in Italy and France.27 Moreover, it has been put forward that such abstinence from corporate activities, as a necessary requirement for limited liability, was already included implicitly in the definition or conception of a silent partner in Florence as well as Bologna.28 Thirdly, the criterion can be defended from a reasonable perspective too. Since the silent partner was fully dependent on the decisions and commercial strategies of the general partner(s), and therefore could not be considered as responsible for the eventual success or failure of the enterprise, his liability had to be restricted to the size of his initial financial contribution. Conversely, it would be unjust to allow a silent partner, whose personal liability was limited, to bind the general partners of his partnership in a joint and several manner. Finally, there is the often-quoted decision of the Great Council of Malines in 1549 regarding Nicolas Le Fer’s alleged limited liability. The Council rejected le Fer’s privileged status because he had been actively involved in the partnership’s activities.29

16Despite the fact that these arguments do not strictly concern actual sixteenth-century practice in Antwerp, the application of the criterion in an Antwerp setting remains justified. After all, a similar kind of abstention could be observed in all previously discussed partnership agreements. Neither the Schetz or Balbi brothers, nor Jan Gamell, Gabriel de Hazu or the stepchildren of Jean vande Vekene were actively involved in the commercial operations and administration of the respective partnerships. Essentially, their involvement remained limited to a mere financial one. Furthermore, the research sample provides an extra argument in favour of the assumption that non-active partners can rightly be considered as silent partners in a limited partnership. In 1596, Peter de Lichte Senior and his son, Jan de Lichte, associated themselves in a three-year trading company.30 The agreement stipulated explicitly that Peter de Lichte Senior was to refrain from all corporate activities. However, the contract contained a clause imposing the joint and several liability on both partners.31 Most probably, the contracting parties were aware of the fact that, because of Peter’s abstinence, their partnership would be considered to be a limited one. Most likely, they incorporated the - normally absent - stipulation on external liabilities in order to renounce from Peter de Lichte Senior’s presumed privileged status.

17For these reasons, one may pitch into the research group anew. As a result, numerous other partnership agreements can be qualified as contracts establishing a limited partnership. The first surviving example dates from 1493.32 In that year, Jan vanden Beke from Brussels and Willem de Luw established a trading company in non-defined goods for an undetermined period of time. Willem’s contribution to the partnership was explicitly limited to the supply of £4, while Jan vanden Beke was supposed to execute the trading activities all by himself. Yet, Willem was allowed to attend these activities ‘if he liked to’.33 Above his managerial efforts, Jan would also contribute goods with a total value of £4.

18Frequently, the combination of a passive and active partner involved a financier who enabled one or more persons with particular trained abilities, but often lacking financial means, to capitalize on these competences. The mutual advantages of such a combo are evident.34 Illustrative in this matter, is the partnership agreement concluded on the 23rd of September between Cornelis van Eekeren, the mint master of Brabant, on the one hand, and the brewer, Nielsen Lissen, on the other hand.35 Van Eekeren embayed 300 guilders with which Lissen was allowed to conduct a brewery business in Het Cruys in Berchem. Lissen was solely responsible for the production of beer, while all potential proceeds were to be parted equally. Even though the partnership was concluded for six years, the contract stated that after three years van Eekeren’s 300 guilders were to be reimbursed. From then onwards, the partnership was to be kept up and running for the following three years by means of the profits already made during the first three years. Similar partnerships between mere money-providers on the one hand and artisans, craftsmen and traders on the other hand, were concluded within the field of leather processing, linen trade, and beer production.36

19Sometimes, the establishment of a (limited) partnership served as a means to generate a pension for former craftsmen or their widows. In 1612, Maria van Ghistel, the widow of the late Jacques Fossart, and up till then owners and managers of the brewery Het Anker in Antwerp, contracted a partnership agreement with Ghysbrecht vande Perre and his wife, Johanna van opden Bosch, to whom Maria had sold the house as well as the brewery immediately after her husband’s death.37 Both parties promised to support the partnership with £600, in cash or goods, each. Nevertheless, it was agreed upon that Ghysbrecht and his wife would be responsible for the brewing activities solely, while Maria’s role in the partnership was merely a financial one. Costs, profits or losses were to be parted equally.

20Often, it is not clear whether the establishment of a partnership between a father and his son(s) was driven by a similar motivation, or that such a partnership was merely a means to promote his son and establish him and his family in the world of business. For example, in the year 1591, the previously mentioned Antwerp merchant in textiles, Peter de Lichte Senior, concluded a five-year partnership agreement with two of his sons, Hans de Lichte and Peter de Lichte Junior. Both contracting parties agreed to contribute an equal amount of cash, and profits or losses were to be shared equally. The trading activities would take place in the house and shop of Peter de Lichte Senior, called Sint-Jan-Baptiste and situated in the Hoogstraat in Antwerp. Both sons and their families were to reside in the same house, where they were expected to conduct the partnership’s business without any intervention of their father.38 One example could be identified in which a father concluded a (limited) partnership with his future son-in-law in order to help his daughter, and her husband-to-be, establish themselves as an independent family. As agreed upon earlier in the contract arranging the marriage between Barbara Schots and Joos Waeye, Jan Schots concluded a partnership agreement with Joos Waeye on the 21st of January 1542.39 The father’s concern to promote his daughter in life is demonstrated by the fact that the eventual profits of the trading company were to be divided equally, even though Jan Schots (£200) had contributed four times as much as Joos Waeye (£50) had done. It was agreed upon that Joos Waeye would execute the trading activities in Antwerp alone by means of a nominal capital totalling £250.

21Another category of silent partners were children. These examples demonstrate an additional motivation to resort to a limited partnership, i.e. a relatively safe investment of the -often inherited - assets of children. In 1592, after the death of Catlyne Gheylincx, her husband, François Leemans, contracted a partnership agreement in the name of his under-aged children, Joos, Eluart and Elizabeth Leemans, with Hendrik de Coninck, a local skin oilier.40 Profits or losses, as well as operational costs, were to be divided pro rata the respective inputs of all participating parties. Hendrik was supposed to execute the entrepreneurial activities single-handed. One may assume that such partnership was set up to invest the money that the children had inherited from their mother.41

5. Conclusion

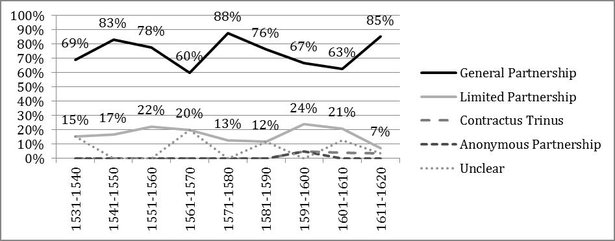

22Despite the obstacles linked to the categorizing of the surviving partnership agreements, it has become feasible to identify a significant number of limited partnerships that were created, established and operative on the Antwerp market in the course of the long sixteenth century. In sum, no less than 25 partnership agreements could be, both explicitly as implicitly, labelled as limited partnerships.42 As demonstrated in chart 1, there are no significant changes to be observed in the number of limited partnerships in the course of the sixteenth century. Apparently, limited partnerships did indeed play a substantial but at the same time relatively modest role in the economic organization of the sixteenth-century Antwerp market. Still, one may not ignore the fact that this study was largely based on notarized partnership agreements and that during the early modern period the use of oral and privately drafted contracts was still a widespread and generally accepted practice among Antwerp merchants.43 In opposition to early modern France, the Antwerp limited partnership did not seem to function as a means to meet the demands of specific social categories like clerics and noblemen in particular.

25The relative steadiness of the limited partnership’s stake in the course of the sixteenth century even suggests the existence of an older, well-established tradition in accomandita-like partnerships predating the year 1530. Nevertheless, such familiarity experienced a considerable and most remarkable relapse from the 1610s onwards. Possibly, the limited partnership, as a means to fructify one’s surplus capital in a relatively safe way, was overtaken by the arrival of a new type of partnership in the Low Countries, i.e. chartered joint-stock companies like the Dutch East India Company (1602) and the Dutch West India Company (1621).

26Regarding the identification of limited partnerships, the abstention-criterion fulfilled a vital role, since most of the extant partnership agreements did not incorporate clauses on the composition of the firma or the external liabilities of its respective members. In this respect, one has to stress that such abstention not necessarily had to be absolute. It implied a complete abstinence from all ‘external’ business activities that involved third parties, yet, silent partners were often allowed to interfere ‘internally’ from an advice-giving point of view as soon as they felt the need to do so.

27Notwithstanding the successful use of the abstention-criterion, scrutinizing the applicability of the firma-criterion, as regards sixteenth-century merchants that were active on the Antwerp market, gave rise to some noteworthy complications. Especially the observation that hardly any of the partnerships agreements incorporated explicit clauses on the composition of the name of the company, casts doubt on the conviction that, in Antwerp too, silent partners were not allowed to appear in the company’s firma in order to guarantee their privileged status, or, more in general terms, that there existed a causal relationship between the presence of one’s name in the name of the company and the measure of his external liability.

28Finally, the present article did indeed confirm the suggested acquaintance of Antwerp merchants with the idea of limited liability, and therefore, it was unable to falsify the hypothesis that the city of Antwerp as well as the diaspora of a considerable part of its merchant community after 1585, played a pivotal role in transferring the idea of limited liability to the northern regions of the European continent and the city of Amsterdam in particular.

6. Annex: List of preserved partnership agreements45

291. Peter van Calmes - Herman Pastoir - Bertelmeeus Gant (LP: 04-11-1482).46

302. Jan Vanden Beke - Willem de Luw (LP: 02-06-1493).47

313. Hendrik Beeckman - Jan Decker (GP: 02-10-1514).48

324. Kilian Rietwieser - Joachim Pruner (GP: 30-12-1525).49

335. Govaert Robrechtsz van Heusden - Reijnaert Muer (LP: 25-09-1526).50

346. Pieter Henricxz alias Wairloes - Frederik Jacobsz vander Meulen, Bernardien Sanicht and their children (LP: 21-08-1532).51

357. Martin Damayo - Pedro de Paredes (GP: 18-02-1535).52

368. Hans Papenbruch - Anselmo Odeur van Eldere - Peter Ronsee - Gerard Pauwels - Nicolaas van Marretsen (GP: 07-06-1535).53

379. Jan van Vlassendonck, Cornelis de Vos and Jan van Damme - Bernard Schoutert (C: 17-06-1535).54

3810. Robrecht van Haesten - Janneke van Zevenberghen (GP: 28-05-1537).55

3911. Hans Spinghele - Claes Stengher (GP: 16-08-1537).56

4012. Arnout Ghysenbrech - Hendrik Garet (GP: 18-02-1538).57

4113. Cornelis van Eekeren - Nielsen Lissen (LP: 23-09-1538).58

4214. Jan Wraghe - Jasper van Gulick (U: 28-11-1538).59

4315. Adam vander Haghen - Adriaan vander Borch - Frans de Buyschere - Karel Crol (GP: 03-04-1539).60

4416. Nicolaas David - Jeronimus vanden Vos (GP: 05-04-1539).61

4517. George Lohoys - Jean Hobreau alias Petit Jean (GP: 20-03-1540).62

4618. Maria Chatoru - Peter de Langaingne and Cornelia Dycx (GP: 15-10-1540).63

4719. Jan Collozy - Robert Cools (U: 24-12-1540).64

4820a. Jan Schots - Joos Waeye and Barbara Schots (LP: 21-01-1542).65

4920b. Jan Schots - Joos Waeye and Barbara Schots - Jan der Kynderen (LP: 21-01-1542).66

5021. François Verjuys - Jan Deem (C: 06-1543).67

5122. Jan van Caster - Thomas Smeyers and Heylwyck Leemans (LP: 09-07-1543).68

5223. Cornelis Rousseau - Lambrecht Michielssen (GP: 16-12-1544).69

5324. Martin Hureau - Nicolas Hureau (GP: 13-03-1545).70

5425. Margriet Kareest - Arnout de Besoit (GP: 03-06-1545).71

5526. Hendrik Peeterssen - Jan de Leeuwe (GP: 13-04-1545).72

5627. Herman Kerstens - Balthasar de Vleminck (GP: 18-07-1545).73

5728. Jan Gheldolff - Cornelis Janssen (C: 02-10-1545).74

5829. Floris de Fonthenis - Jennin van Ranst (GP: 26-04-1547).75

5930. Jan van Eynde - Joos Verbeken (GP: 20-12-1549).76

6031. Domingo de Rossano - Michael de Paulo - Michael Angeli Francisque (GP: 08-02-1550).77

6132. Willem Borremans - Jan Verheyen (GP: 09-06-1550).78

6233. Christiaen Suyderman - Herman van Reden (GP: 27-11-1550).79

6334a. Jaspar, Melchior and Balthasar Schetz - Christoffel Pruynen - Adriaen van Hilst (LP: 01-12-1552, 3/4-05-1553).80

6434b. Jaspar, Melchior, Balthasar and Koenraad Schetz - Christoffel Pruynen - Adriaen van Hilst - Jan Vleminckx (LP: 16-03-1558, 03-07-1560, 03-03-1561).81

6534c. Melchior, Balthasar and Koenraad Schetz - Christoffel Pruynen - Adriaen van Hilst - Jan Vleminckx (LP: 04-03-1563, 26-03-1568).82

6635. Christoffel Guinget Junior - Pauwels Rethan (GP: 15-12-1552).83

6736. Cornelie Boots - Melchior Braem (GP: 18-03-1555).84

6837. Aert die Cleyne - Mariken Plucquet (GP: 10-05-1556).85

6938. Alaert de Cock - Sebastiaan Reynenborch (GP: 27-03-1557).86

7039. Jan Gamell - Pauwel van Houte - Peter Sobrecht (LP: 13-04-1558).87

7140. Toussain Vassal - Robert de Neufville (GP: 11-11-1558).88

7241. Johan van Weerden - Magnus Friessch (GP: 27-05-1560).89

7342. Christiaen Lambrechts - Christoffel Henricx (GP: 12-09-1560).90

7443. Guillaume Borremans - Jan Verheyden (GP: 06-05-1561).91

7544. Melchior Wolcker - Thomas Chanata - Peter de Zeelander (GP: 23-12-1561).92

7645. Anna van Eerdborne - François Stelsius (GP: 14-07-1562).93

7746. Thomas Molinel - Anthoni Couvreur (U: 1562).94

7847. Cornille de Bomberghen and Christoffel Plantijn - Charles de Bomberghen - Johannes Goropius Bekanus - Jacques de Scotti (LP: 26-11-1563).95

7948. Lucia Vermeulen - Hans Huybens Junior (GP: 03-01-1573).96

8049. Arnout Vermeren - Nicolaes de Groote (GP: 02-07-1577).97

8150. Balthasar Belot and Catherine Bals - Peter Belot and Marie Bals (GP: 19-08-1578).98

8251. Elisabeth Wouterssen - Anna Roovers (LP: 05-09-1578).99

8352a. Boudewijn Breyel - Bernard Lunde - Gielis du Merchy (GP: 15-09-1579).100

8452b. Boudewijn Breyel - Bernard Lunde - Gielis du Merchy (GP: 15-09-1579).101

8553. Balthen Diericx and Dirk Diericx - Jan vanden Dale (GP: 06-11-1579).102

8654a-b. Jan van Eersbeke alias vander Hagen - Jan Willemssen and Hillebrant Fuys (GP: 28-12-1579).103

8755. Peter Thunen - Nicolaes Thunen - Jan van Thunen (GP: 14-01-1580).104

8856. Gielis Nys - Hans Verspreet (GP: 1581).105

8957. Octaviaan Mercx - Hendrik de Neve (LP: 20-10-1582).106

9058. Cornelis vanden Putte - Hendrik vanden Putte (GP: 20-08-1583).107

9159. Maarten della Faille - Johan Borne - Johan de Wale - Thomas Cotteels (GP: 26-09-1583).108

9260. Hans Merchis - Roctus Nys (U: 16-11-1583).109

9361. Hans Laoust - Cornelis de Hase (GP: 27-04-1584).110

9462. Guillaume Heffels - Gerard Heffels - Hans de Coninck (GP: 15-03-1585).111

9563. Jacques van Homssen - Jaspar van Homssen (GP: 17-09-1585).112

9664. Peter de Lichte - Jacques Taelman (U: 09-11-1585).113

9765. Melchior Christoffels - Jan Praet (GP: 06-01-1586).114

9866. Jan vanden Berghe - Martin de Rantre and Hans vande Meere (GP: 11-01-1586).115

9967. Gabriel de Haze - Dirk Verhoeven (LP: 18-01-1586).116

10068. Hendrik Pelgrom - François Pelgrom (GP: 24-01-1586).117

10169. Melchior Botmer and Hans Strader - Jan vanden Berghe (GP: 03-11-1587).118

10270. Cornelia Priusstinck - Sebastiaen de Smit - François van Dyck (GP: 27-01-1588).119

10371. Chrisostomus Scholiers - Jacques Andries - Jan van Immerseel (GP: 31-05-1588).120

10472. Joris van Bellijn - Jan Pels - Vincent Verstraten (GP: 03-02-1590).121

10573. Melchior Rensen - Hans Martyn (CT: 23-01-1591).122

10674. Peter de Lichte Senior - Hans de Lichte and Peter de Lichte Junior (LP: 25-01-1591).123

10775. Balthasar Kemp - Peter Wiebouts (GP: 03-09-1591).124

10876. Simon Jacobs - Jacques Jacobs (GP: 18-07-1592).125

10977. Hendrik de Coninck - Joos, Eluart and Elizabeth Leemans (LP: 30-10-1592).126

11078. Lucia Sannen - Nicolaes Peeters and Anna Wynants (GP: 16-01-1593).127

11179. Joos dela Flie and Catharina Becx - Hans van Ype (GP: 11-03-1593).128

11280. Alexander Bouwens - Cornelis Bouwens (GP: 02-08-1593).129

11381. Michiel Verhagen - Hans Hermans - Maarten van Laecken - Anthoni van Laecken – Anthoni Mathys (GP: 30-10-1593).130

11482. Jaspar Doncker - Melchior Doncker (GP: 24-01-1594).131

11583. Lucas Sabot - Abraham Sabot (LP: 25-02-1594).132

11684. Hans Scholtens - Jan van Anvyn (GP: 10-03-1595).133

11785. Peter de Lichte - Jan de Lichte (GP: 01-04-1596).134

11886. Alexander vanden Steene - Jacques Heyns - Vincent Ingelgrave - Paschier Ingelgrave (GP: 23-01-1596).135

11987. Jacques Wynman - Cornelis Rogiers - Cornelis van Uffele (AP: 18-06-1596).136

12088. Jehan van de Vekene - Marie, Suzanne, Anne and Elias Fruict (LP: 07-12- 1596).137

12189. Louis Scheurbroot - P. de Prez (GP: 1597).138

12290. Pauwels and Peter Lanceloots and Joos Smit - Adriaen de Wyse, Hubrecht Peeters, Jan van Yperen and Christoffel Quaeyribbe (LP: 16-01-1598).139

12391. Erasmus Hoen - Martin Poullin (GP: 16-02-1598).140

12492. Abraham Seeldrayers - Gielis van Grimbergen (GP: 17-12-1598).141

12593. Melchior Peeters - Adam Verjuys (- Hendrik Laureyssen) (GP: 13-07-1599).142

12694. Bonifatio Cambiani - Jacques de Paigee (GP: 08-03-1601).143

12795. Nicolaes Fuzee and Anna van Ham - Johanna Spillemans (LP: 11-04-1601).144

12896. Johanna van Dyck - Adriaen Delen (GP: 24-05-1602).145

12997. Catharina van Dyck - Arthur vander Venne (GP: 26-10-1602).146

13098. Rudolphus Reenis - Richardus Machinus - Johannes Rallins - Robertus Benfielt (GP: 16-03-1604).147

13199. Johan Taedts - Matthias Michaeli - Pieter van Boetselaer (U: 19-03-1604).148

132100. Lorenzo Maggioli - Giovanni Francesco, Bartolomeo and Jeronimo Balbi (LP: 12-06-1604).149

133101. Hans van Veerle - Jaspar de Zettere (GP: 02-06-1605).150

134102. Jacques Calvaert - Guillaume Calvaert (U: 21-08-1606).151

135103. Lenaert Lenaertsen - Albrecht Tol (GP: 15-11-1606).152

136104. Andreas vanden Brande - Jacques Pagie (GP: 16-01-1607).153

137105. Alexander Goubou - Jan Goubou - Rinaldo Hugens (GP: 24-04-1607).154

138106a. Jacques Tacx - Melchior Arents (GP: 29-11-1607).155

139106b. Jacques Tacx and Melchior Arents - Balthasar Tacx (GP: 22-12-1607).156

140107. Francisco Fernandes Duarte, Jacques Gysbrechts and Lucas Remond de Jonge - Lenaert Lamentoni (GP: 18-12-1607).157

141108. David Ferdinand du Sart - Jan de Mayere (GP: 12-01-1608).158

142109. Marie vanden Perre - Jacques Bollaerts and Anna Goossens (GP: 28-04-1608).159

143110. Hendrik Meys - Gabriel Meys (LP: 11-06-1609).160

144111. Giacomo Antonio Annone - Hannibale Bosselli (LP: 07-09-1609).161

145112. Joos de Smidt - Jan de Nollet - Jan Desmarez (LP: 11-07-1609).162

146113. Marie Vermeulen - Gilles de Wilde (GP: 06-08-1609).163

147114. Guillaumme Calvaert - Gilles dela Faille (GP: 22-08-1609).164

148115. Barbara Verheyen - Sebastiaen Meeus (U: 09-09-1609).165

149116. François Johnssen - Jacques de Paige (CT: 10-10-1609).166

150117. Pierre Bergeron - Denis Lermite, Gonsalo Gomez, Gilles Deegbroot and partners (GP: 24-09-1610).167

151118. Hans van Moockenborch - Gielis de Mont Junior (GP: 09-08-1611).168

152119. Melchior de Rancourt - Hans de Setter (GP: 29-11-1611).169

153120. Barbara Andriessens - Guilliamme Goyvarts and Clara Charle (GP: 21-04-1612).170

154121. Maria van Ghistel - Ghysbrecht vande Perre and Johanna van opden Bosch (LP: 30-07-1612).171

155122. Hans de Crock - Hans Smits (GP: 07-01-1613).172

156123. Jacques Engels - Jacob Stevenssen and Anthonis Meeussen (GP: 11-02-1613).173

157124. Gabriel Fernandez - Hendrik van Paesschen (GP: 26-06-1613).174

158125. Clara Moens - Jacques Goos Junior - Anthoni van Battel (U: 07-09-1613).175

159126. Jaspar van Blois - Karel Batkin (GP: 02-10-1613).176

160127. François Bonecroy - Guilliamme Bonecroy (GP: 20-06-1614).177

161128. Cornelis Peeters - Hans Meil and Katlyne Goyvaerts (LP: 1614).178

162129. François Doncker - Jan Doncker and Lambrecht Greyns (GP: 04-02-1615).179

163130. Jacques Hermans - Gerard Wilrycx (GP: 19-02-1615).180

164131. Peter van Ceulen - Cornelis Engelandt (CT: 07-05-1616).181

165132. Jan van Honssem Junior - Gerard van Gherwen (GP: 18-07-1616).182

166133. Jacques Boon and Anna Bosschaerts - Jacques vanden Velde (GP: 22-09-1616).183

167134. Filip de Potter - Peter Fredericx (GP: 29-09-1616).184

168135. Jan Thieuliers - Jan van Coevoorden - Hans van Eerdenborch (GP: 1616).185

169136. Anthoni Jonckbouwens and Johanna Pluym - Bernard Sterck (GP: 02-01-1617).186

170137. Bartolomeus Smeerpont - Maarten Joossen (GP: 02-01-1618).187

171138. Jan van Keerberghen - Jeronimus Verdussen Junior (GP: 14-05-1618).188

172139. Gabriel Fernandez - Artus vanden Bogaerde and Jan vanden Bogaerde (GP: 08-03-1619).189

173140. Hans Boey - Hans vande Verre (GP: 22-03-1619).190

174141. Gilles Hanecart Junior - Jan Mastelin (GP: 08-06-1619).191

175142. Clara Moens - Jacques Goos Junior - Anthoni van Battel - Rodrigo Mattias - Jan Baptista Goos (GP: 07-12-1619).192

176143. Peter Jacobs - François de Hayaux (GP: 08-10-1620).193

177144. Jan Hasius - Richard Versteghen - Lenaert van Lom - Peter Meybosch (GP: 07-09-1620).194