- 1 – From numbers to culture: introduction

- 2 – Administrative law textbooks: from the French predominance to the slow consolidation of the Brazilian literature

- 3 – One cosmopolitan journey in two phases: nationality of authors cited in texts on expropriation from law journals

- 4 – Prominence of one author or value of a whole country? The impact of legal cultures

- 5 – Sources of law and means of diffusion of the legal culture: the roles of doctrine and case-law in monographic books on expropriation

- 7 – Cornerstones: most cited authors in texts on expropriation in law journals

- 8 – The implicit code of the Brazilian administrative legal culture: final remarks on a deeply connected scholarship

1Tive muitas vezes occasião de deplorar o desamor com que tratamos o que é nosso, deixando de estudá-lo, para somente ler superficialmente e citar cousas alheias, desprezando a experiencia que transluz em opiniões e apreciações de Estadistas nossos (...). O estudo das nossas instituições tem-me convencido de que, felizmente, as largas e liberaes bases em que assentão são excellentes: Quantas nações se darião por muito felizes, possuindo a metade daquillo com que nos favoreceu a mão amiga da Providencia1.

Visconde do Uruguai, 1862, pp. VIII; XV

1 – From numbers to culture: introduction

2Some valuable works have already been written on general features of Brazilian administrative law at the empire (1822-1889) and the first republic2 (1889-1930). However, we still lack a deeper understanding of how lawyers wrote their texts and the conditions of their intellectual universe. In other words, there are studies on specific legal institutes (CORREA, 2013; COELHO, 2016), on legal education (RAMENZONI, 2014), and on the everyday affairs of crucial institutions such as the Council of State3 or the Supreme Court of Justice4, but little has been written on the body of information available to jurists, and on how they manufactured these data to create their texts. The problem persists even considering the Brazilian legal historiography more broadly. Most scholars have accepted the reading by Ricardo Fonseca (2006) of Carlos Petit’s (2014) ideas that the 19th century was marked by the slow shift from an eloquent model of a jurist with a broad culture to a technical5, legalist law scholar. But little is known of more concrete details of the texts produced by lawyers; whom they cited, which texts they read, which criteria were used to select information etc.

3A first description of the (doctrinal) sources available to Brazilian jurists is offered by Sônia Regina Oliveira (2011). However, she only described the scholarly literature on private law published in the journal O Direito in the late Empire. We still lack a discussion on the relations between the different sources6, as well as an analysis of other fields of legal knowledge. Martins and Albani (2020) analyzed one particular aspect of ecclesiastic law and explored case-law, but their approach was too specific to allow complete conclusions. Walter Guandalini Jr. (2019) published an interesting work on the sources of law used by Brazilian textbooks of administrative law. However, he mainly concentrated on legislation – doctrine was mostly treated in a generalist way. There is some impression left in the air that scholars cited French and Italian laws, that some foreign institutes “seemed to have inspired” Brazilians (DI PIETRO, 2006, p. 19), though this is not developed and no one knows the proportion of citations, what they meant to Brazilian scholarship and why shifts in intellectual references happened. I intend to (partially) bridge this gap.

4The objective of this work, therefore, is to understand the textual archive (Arquivo textual, HESPANHA, 2010, p. 114) of Brazilian jurists who wrote about administrative law between 1859 and 1930, focusing on legal scholarship and case law. With which texts did they engage, and which were the cultural criteria used in selecting these texts? Which foreign legal cultures were most esteemed? Which journals were most frequently consulted? Which text genres were referenced? My goal is to decipher the cultural parameters employed by Brazilian administrative law scholars to select information and shape their texts.

5I started the analysis in 1857, the same year when the first textbook of administrative law was published in Brazil7. In 1889, the form of the state changed from an empire to a republic, with important institutional consequences: the former highest court, the Supremo Tribunal de Justiça, was transformed from a simple cassation court into a supreme court8; federalism9 was introduced, many law schools other than the two imperial ones were created10, the administrative justice was extinguished11 etc. We will then be able to see if and how those institutional changes affected the writing of administrative law. I ended the analysis in 1930 when a coup d’état overthrew the first republic and paved the way for the replacement of a mostly liberal order, with an incipient interventionist state12, by a model of state with a clearer role in the economy.

6My methodology was a bibliometric analysis, and my underlying theoretical approach was the perspective of legal culture. I shall discuss why and how I used those two approaches before I would proceed with the discussion of my research.

7Bibliometrics can be understood as the collection and analysis of quantitative data regarding authors, citations, and means of dissemination of texts produced by a given field of knowledge. The potential of this approach for legal history is stressed by Nader Hakim and Annamaria Monti (2018, p. 7). As they stated, "since the legal text is a semiotic system since it is the result of a collective bricolage, it is possible to dissect it to understand its structures and foundations. It is then necessary to enter into [the] text to analyze its internal sources and external networks"13. This approach reveals vestiges of the intellectual efforts made by authors before the actual writing - what they read and the importance he placed on it - and the constraints he had to face – works or languages he could not read, for instance.

8Furthermore, "these references and citations are also traces of intellectual exchanges and draw a genealogy not of influences, but of the structuring and justification lines of a discourse"14. As Barenot (2018) shows, it is possible to track previously unknown networks. Frequently, we discover that the most sophisticated authors, usually cherished by historiography, were not always the most frequently read in everyday life.

9The bibliometric approach, by exposing broader trends, can challenge commonplaces with empirically verifiable data - for example, the so-called influence of the French legal culture on Brazilian administrative law. A closer look into what was cited can illuminate the reading practices of a single person or a social group, albeit in a fragmentary manner: we can discover which books were most widely praised and the authors who fell into oblivion. After all, the lack of sources often prevents the reconstruction of the material circulation and chain of distribution of writings, as done by Robert Darnton (1990) and many others. Bibliometric approaches can counter these blind spots and reveal the textual network of references employed by an author in his professional life, which value he attributed to certain ideas, and how different intellectual networks were formed. Such analysis can therefore complement book history. In addition, quantitative data, combined with digital humanities, provide a more accurate visualization of the relationships between different sets of information and thus helps the researcher to identify general trends15. In short, if every single text is forged in close interaction with other texts, the only scrutiny of textual networks can entail a broader understanding of the historical meaning of any writing.

10Of course, this type of research faces some constraints. Citations can assume different connotations: they can structure an argument, merely reinforce a point in a footnote, allow a simple display erudition, or even provide a negative counterexample. It is hard to unravel the option that lies behind the mention of an author – sometimes, it is even impossible16. Therefore, the quantitative perspective of bibliometrics cannot replace the traditional techniques of close reading (HAKIM; MONTI, 2018, p. 9). As Barenot (2018, p. 14) says, "bibliometry is not an end in itself, but a preliminary task; it is inscribed within a methodology of identification and prior classification of authors and works"17. As Hakim and Monti (2018, pp. 9-10) said, it allows new phenomena to be revealed and old intuitions to be (dis)proved; but, above all, it is capable of launching new hypotheses to be tested.

11Bibliometrics is a fundamental complement to book history18. This field deals with three dimensions: production, circulation, and reading of prints; the latter remains the most elusive part of the history of prints (DARNTON, 2010, p. 121). Between owning a book and reading it, lies an incommensurable distance. But bibliometrics can give clues on how this frequently mysterious process happened19. We also can further the classical scheme of the circulation of writings proposed by Robert Darnton (2010, p. 127) analyzing how texts were integrated into a textual network. Bibliometrics, therefore, enlarges the field of book history by not focusing on how the ideas of the author were taken in a material form to the reader: instead, it reveals how an author was also a reader interconnected with several other texts.

12How shall we read the data extracted in the quantitative analysis? The first piece of advice is to avoid the temptation of seeing in citations the "influence" of one country upon another. This perspective of international connections can only yield modest results, due to the generic nature of the very notion of “influence”20, which “emphasizes the law itself and not the problematics of the receiving country” (SOLEIL, 2014, p. 323). As Soleil points out, it was not the French law that influenced “Brazil, Switzerland or Greece”, but the international exchanges “put into play in complex ways the needs of the importing elites, the ambitions of the exporting country, the admiration for this country, the way and qualities of the law” (SOLEIL, 2014, p. 323). The concept of cultural translation21 is more useful than the one of influences, for it highlights that the contact between cultures does not result in a simple transfer of practices or data from one social group to another: the “receivers” reinvents the previous knowledge. Legal ideas never remain the same after crossing borders: they are recreated to face new problems and to be accommodated in their new geographical or temporal context. I will analyze these context changes helped by the idea of legal culture; that is, by an anthropological approach to law. This means to emphasize the symbolic dimension of social practices; the objective, then, is to grasp the connections between certain ideas and how they constitute a coherent system of interpretation of the reality – and, therefore, parameters of action over it. The interpretative task of the anthropologist-historian-jurist, then, is to transform into a familiar idea this hidden code of action that, otherwise, would be distant and perhaps inaccessible as said by Clifford Geertz (1989)22. Moreover, the textual archive mobilized by an author interacts with a pre-existing mindset: authority, prestige, exoticism, and other symbolic assumptions are defied and/or enhanced in order to convince the reader. The anthropological approach, building upon the concept of culture, seeks to decipher this implicit code of values sustaining each legal culture, each author, each discipline. This activity is analogous to what Quentin Skinner (2001) proposes: he asks himself what an author is doing as a speech act while using a certain idea; the question I propose is "what the author is doing when quoting a certain text". – Is this sentence a question?

13My analysis was developed in two phases. First, I extracted the citations from the Brazilian textbooks of administrative law; I excluded the monographic works from this phase because the particularities of a certain area could distort the sample (part 2). The second step is a case study of citation practices in texts on expropriation23 (desapropriação). By winnowing the analysis to a specific field, it was possible to examine not only monographic books but also articles and case law published over a very long period of time. Thus, it became possible to compare different literary genres. I analyzed texts on expropriations published in law journals (parts 3-5 and 7) and in monographic books published on expropriation (part 8).

14Brazil was – and still is to this very day – a huge country, with dazzlingly diverse peoples, environments, and, of course, legal practices. I must, then, clarify what I assume as “Brazilian” for this study. As it will be clearer later, I focus on the published elements of legal culture, namely books and law journals, that circulated across most of the country. They claimed to be representative of the whole of Brazil, as they analyzed national laws and published the “most important” decisions of all courts. This was obviously an illusion. Being published mostly in the economic and cultural/political capitals – São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro – they reflected what was important in the “center” of the nation. The urbanized centers where the presence of the State could be felt more consistently also provided the most fertile soil for the development of administrative institutions. Therefore, I analyzed the published and disseminated legal culture, which claimed to be Brazilian and was recognized as such, though it received unequal input from different parts of the country. The administrative law I analyzed does not correspond to the lived reality of the entire nation: conversely, it is part of an aspired unity that was presented as such. A fiction, however, that was precisely what lawyers could access when they purchased books, entered libraries, or were in the classes of law schools. I shall leave to future research to investigate if and how the unified, filtered administrative law of the “central” legal thought differed from the legal practices of the single provinces/states. Articulating general and specific features, books and articles, legal culture, and bibliometric analysis, it will be possible to identify fundamental characteristics of Brazilian administrative law over more than 70 years, and how they changed with the institutional transformations that happened over time. However, due to its eminently initial character, this study seeks mostly to launch hypotheses and prepare the ground for future research - not to provide definitive answers.

2 – Administrative law textbooks: from the French predominance to the slow consolidation of the Brazilian literature

15Any science is expressed employing a wide complex of communicative practices, each one aiming at particular ends. The “science of textbooks” aspires to consolidate the knowledge of a given field and to present the most solid information and recognized practices (FLECK, 2010, p. 173 ss.). In this first section, I examine the textbooks of administrative law published in Brazil during the Empire and First Republic (1822-1930) to grasp what was presented as the approved face of administrative law to students and practitioners.

16I identified the authors cited in the 10 Brazilian textbooks of administrative law published during the selected period24 and their nationalities; this will help me to understand which legal cultures were seen as the most prestigious in the Brazilian administrative literature. Each citation was individually counted, that is, I counted every mention to a given book/author that appeared in the analyzed text body. The exception was the book of Antônio Joaquim Ribas, which, despite presenting a list of references at the beginning, does not mention them in the text. These bibliographies are often misleading: in books such as those by Alcides Cruz and Viveiros de Castro, many works cited in the body of the text are omitted from the initial list presented by the author.

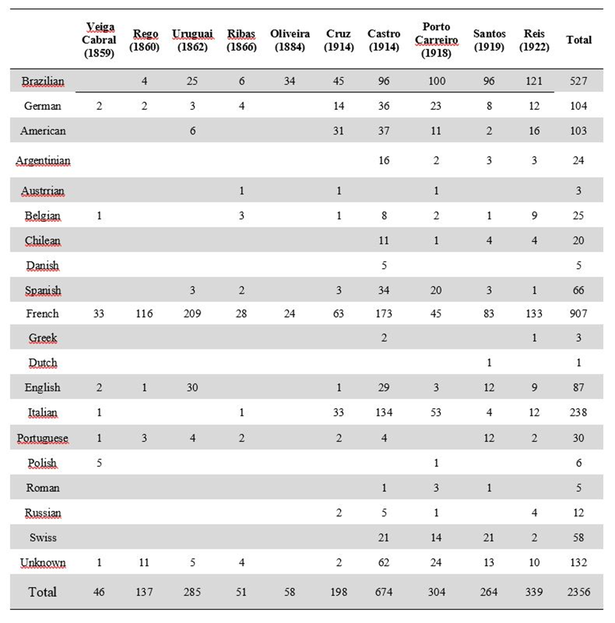

17The results of the analysis were:

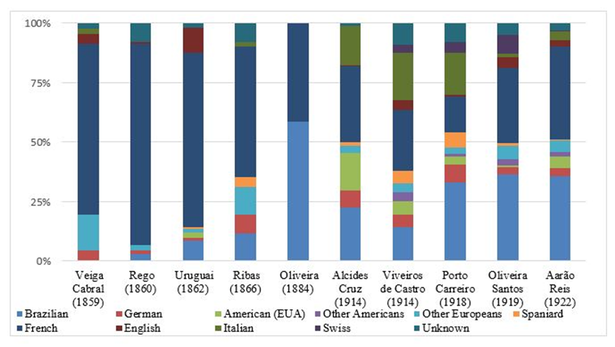

18 Chart 1 Proportion of Citations by Nationality of the Authors cited in Brazilian textbooks of administrative law (1859-1922)

Chart 1 Proportion of Citations by Nationality of the Authors cited in Brazilian textbooks of administrative law (1859-1922)

19The presence of French authors is striking. They correspond to almost 80% of citations in the 1860s, precisely the decade when the first Brazilian books were published. The dawn of Brazilian administrative law featured the shadow of the well-established French scholarship. In the South American empire, this discipline was created only in 185425, and there is no surprise in finding Brazilians heavily relying on French authors, who, after all, was the first to deal with the subject26. Nonetheless, even after the body of national works available grew, France remained as an important reference: before the work of Porto Carreiro (1918), the French were more cited even than Brazilians themselves, with the solitary exception of the book of Oliveira (1884).

20Numbers tell much, but frequently humans cannot hear them. To better grasp what the data presented above can reveal, I insert the data on citations in Palladio27, a data visualization software of digital history developed at the University of Stanford and freely available on the internet. I organized the data in a table in which each file had two cells, one representing the book where I found the citation and a second one, representing the author cited. I inserted this table in Palladio, producing a series of graphs, in which nodes represent the authors and edges represent citations; the darker nodes represent the authors of the handbooks and the lighter nodes represent the authors cited in them. Let us see what we can find with them.

21The first graph show the citations of books published in the Empire:

22 Graph 1 Citations in Brazilian handbooks of administrative law published in the empire. In darker gray, the Brazilian books on administrative law; in lighter grey, the authors they cited.

Graph 1 Citations in Brazilian handbooks of administrative law published in the empire. In darker gray, the Brazilian books on administrative law; in lighter grey, the authors they cited.

23The first impression we get is how the Viscount of Uruguai mentions authors that the others do not cite; he had a more diverse intellectual repertoire, while Ribas, Veiga Cabral, and Rego had a similar number of authors unshared with the other administrative law scholars. The Epítome de Direito Administrativo, from José Rubino de Oliveira, has almost no exclusive references; this probably results from the eminently educational nature of the work: in the foreword to Epítome, Oliveira says it was written „with speed“ for the students, „to ease the study of the disciplines“, meaning that he not always „could read what I wrote“ before delivering the manuscripts to the editors to be „printed and distributed as fascicles“ (OLIVEIRA, 1884, s. p.). Such work must strive more for clarity than for and erudite display of intellectual prowess, and the graph shows it.

24The Viscount of Uruguai had different objectives. In the famous preamble of his Ensaio de Direito Administrativo, he clarifies that he had recently traveled to France and England and was amazed by their progress; but these countries did not draw their civilization from technical engines but from their solid institutions. His work aimed to present Brazilian administrative law within a wider context: he claimed to have read „almost all writers that wrote about administrative law in France“ and compared the Brazilian institutions with those „in Portugal, Spain, Belgium, England, and the United States“ (URUGUAY, 1862, p. IX). He was most attentive to adapting the foreign institutions to the particular situation of Brazil (SILVEIRA, 2020). Different works, with different intentions, cited differently.

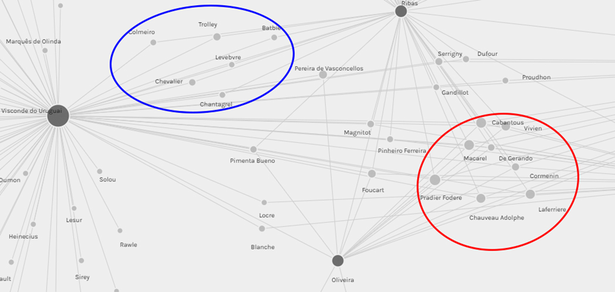

25Now, shall we look at the center of graph 1:

26 Graph 2 Detail of the graph on the citations of Brazilian handbooks of administrative law published during the Empire. In darker gray, the Brazilian books on administrative law; in lighter grey, the authors they cited.

Graph 2 Detail of the graph on the citations of Brazilian handbooks of administrative law published during the Empire. In darker gray, the Brazilian books on administrative law; in lighter grey, the authors they cited.

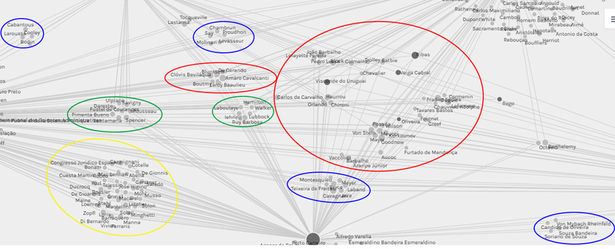

27Now at the center of the graph, we can concentrate on what was commonly cited by the handbooks, and not what was exclusive of one or another. The blue circle highlights the common citations of Ribas and Uruguai, the pair that shared the most citations that were not cited by others. This can be explained by their being published in a similar period (1866 and 1862) and the two authors were the only ones with political careers, living in Rio de Janeiro.

28But the most interesting highlight can be found in the red circle: the authors cited by all Brazilian handbooks of administrative law. Cabantous, Vivien, Macarel, Pradier Foderé, De Gerando, Cormenin, Laferrière, and Chauveau Adolphe: they are the founding fathers of French administrative law, authors of the most famous manuals of the dawn of the discipline. They formed a sort of „canon“ for the Brazilian handbooks: they were cited by every single one of them, though not always our scholars engaged with the thought of their French counterparts. To keep with a single example of what was not an odd practice, the Viscount of Uruguai (1862, p. 6), when he justifies his division of public law in administrative and constitutional law, says: „This division is adopted by notable writers such as Laferrière, Dalloz, Foucart, Cabantous, and others, though some separate what they call public law in a narrow sense“. He does not discuss properly the ideas of any of the writers: he cites them to show the breadth of his research. Laferrière, Cabantous, and the others are more like totems, the forefathers that must be remembered, but not always listened to.

29Anyhow, this cannon gave some sort of consistency to the field: in this difficult age of pioneers, it was important to have a firm soil to build the foundations of Brazilian administrative law. Shared references (and, sometimes, shared ideologies), assured that the different texts were talking about the same things, speaking in the same language, and, for the first time, crafting the cradle of Brazilian administrative law.

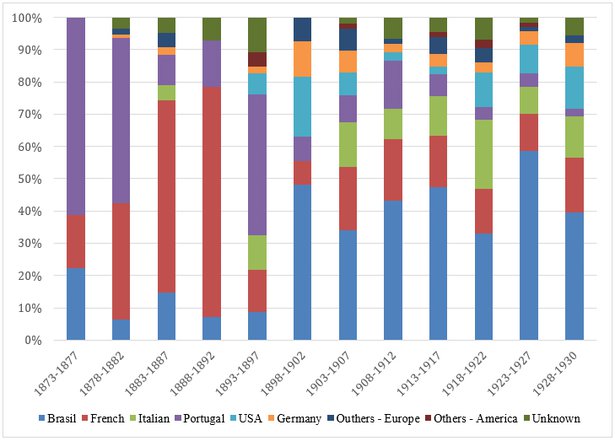

30In the Brazilian republic, as chart 1 suggested, things changed. Let us compare the previous findings with graph 3, concerning the Brazilian handbooks of administrative law published during the republic:

31 Graph 3 Citations in Brazilian handbooks of administrative law published in the First Republic. In darker gray, the Brazilian books on administrative law; in lighter grey, the authors they cited.

Graph 3 Citations in Brazilian handbooks of administrative law published in the First Republic. In darker gray, the Brazilian books on administrative law; in lighter grey, the authors they cited.

32The number of unshared citations grew, especially if we look at Viveiros de Castro and, to a lesser extent, to Aarão Reis. This is, to some extent, a surprise: Reis had no legal education, but was an engineer, and wrote his book for his chair of administrative law at the Engineering School of Rio de Janeiro; one could imagine that he would have a whole body of works unknown to the other four authors, all of them jurists - but this was not the case. The author with more exclusive references was Viveiros de Castro, something that is in line with his intentions: he claims to have done „a work of promotion of legal doctrines, choosing among the many theories those that seemed to be more true or less debatable, illustrating the lessons of the masters (...) with our examples, and exploring the rich vein of the comparative legislation, preferring the countries with the organization most similar to ours“, especially considering the „deep changes produced upon administrative law due to the admirable works of German and Italian publicists“ (VIVEIROS DE CASTRO, 1914, p. 14-15).

33What was the effect of adding these new elements to the old, imperial trunk of French authors? In graph 4, which zooms in the center of graph 3, we can find out.

34 Graph 4 Detail of graph on citations in Brazilian handbooks of administrative law published in the First Republic. In darker gray, the Brazilian books on administrative law; in lighter grey, the authors they cited.

Graph 4 Detail of graph on citations in Brazilian handbooks of administrative law published in the First Republic. In darker gray, the Brazilian books on administrative law; in lighter grey, the authors they cited.

35First, we can notice more clusters of citations shared only between two authors, which are circled in blue; they are diverse and do not allow any conclusions on affinities between the authors. The exception is the Cluster highlighted in yellow, comprising works cited by Viveiros de Castro and Porto Carreiro. Carrero was the first one to publish a book after the Tratado of Viveiros de Castro, meaning that he incorporated many of the references from Castro. Many of the authors inside the yellow circle are actually Italian (e.g. De Gioannis, Ferraris, Minghetti Carmignani, etc) and some are Germans (Zopfl, Mohl, Roesler, etc), showing that both admired the new masters of administrative science. The structure of the graph gets more complex as some independent clusters of citations are shared between three authors – those highlighted in green. And many of those cited are not new works – the leftmost circle, for instance, includes Ulpian, Savigny, Rousseau, Pimenta Bueno, and Fustel de Coulanges. These green clusters can be seen as a „second-tier canon“, of authors widely known, but not always cited. Finally, we have the red circles highlighting the citations made by at least four authors. Almost all of the „imperial canon“ is still here: Cormenin, Pradier Foderé, Laferrière, etc. But there are two important additions. First, Brazilian authors: Visconde do Uruguai and Ribas, the most prized imperial administrative law scholars, and republican jurists as Clóvis Beviláqua, Carlos de Carvalho, Pedro Lessa etc. Second, the new German (Bluntschli28, Von Stein, Mayer29) and Italian scholars (Orlando, Chironi, Meucci), coupled with other references from Europe and beyond (Hauriou, Posada, Goodnow).

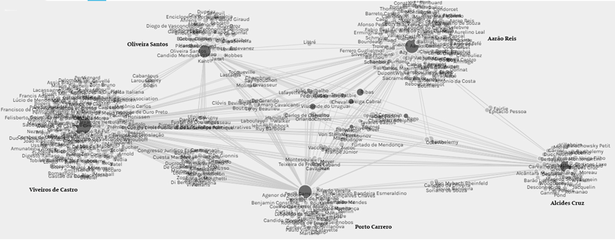

36A fuller analysis can be obtained with the complete image of all the authors of administrative law in Brazil, as shown by graph 5:

37 Graph 5 Citations in Brazilian handbooks of administrative law published in the Empire and the First Republic. In darker gray, the Brazilian books on administrative law; in lighter grey, the authors they cited.

Graph 5 Citations in Brazilian handbooks of administrative law published in the Empire and the First Republic. In darker gray, the Brazilian books on administrative law; in lighter grey, the authors they cited.

38This graph gives us the full picture of the citations made by Brazilian administrative law scholars between 1859 and 1922. On the right, we find the handbooks from the empire, while on the left we can see the republican ones. Comparatively, it is easy to see that the former cite far less frequently than the latter, which is probably related to information circulating less due to a more precarious educational system, fewer libraries, etc.

39The center of this graph, highlighted in the following picture, allows us to draw interesting conclusions:

40 Graph 6 Detail of the graph on citations in Brazilian handbooks of administrative law published in the Empire and in the First Republic. In darker gray, the Brazilian books on administrative law; in lighter grey, the authors they cited.

Graph 6 Detail of the graph on citations in Brazilian handbooks of administrative law published in the Empire and in the First Republic. In darker gray, the Brazilian books on administrative law; in lighter grey, the authors they cited.

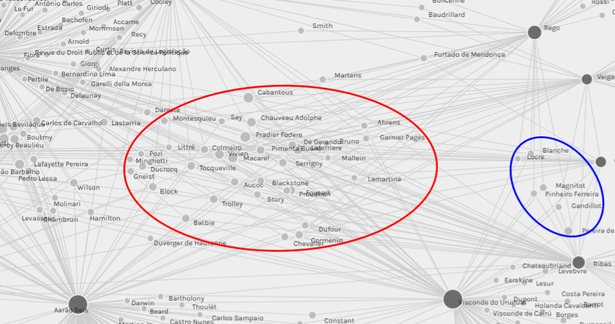

41The red circle shows the authors between the nodes corresponding to the clusters of republican and of imperial handbooks. That is, they comprise the central canon transmitted from the Empire to the First Republic, a sparkle of continuity between those two different times. Almost all of them are French. Very few authors in this new graph lie between the imperial handbooks only – they can be found in the cluster highlighted in blue. They correspond to authors shared between more than one handbook in the empire but left out of the republican canon; their rareness indicates that most of the imperial canon was deemed central for the Republican authors and that the new German and Italian authors were coupled with rather than replaced the previous French group. Though comprising few authors, the very existence of this blue circle reminds us that scholarly disciplines are made not only of memory but also of forgetting.

42Comparing these three graphs, we can follow administrative law moving from a simpler to a more complex structure. In the Empire, there were mostly two types of references: exclusive of an author and shared by all of them. In the Republic, we have multiple strata: exclusive citations, those shared between two or three authors, and those shared between most of them. The framework of nationalities also gets more complex: from a prevalence of French jurists to a more variated group of first French and Brazilian authors, then Italian and German jurists of the new administrative sciences, and finally other, less related authors.

43Another important way to see the changes in Brazilian administrative law is by calculating the density of the graphs. Density in graph science corresponds to the division between the number of edges and the number of possible edges (LIZARDO, JILBERT, 2020, 2.9). In the case of our graphs, the more dense one is, the more handbooks share their citations among them. The imperial graph is slightly more dense (0,270303..) than the republican one (0,268805)30. Though the imperial handbooks had a more stable canon, probably the several „sub-canons“ of the republican period, shared between only two or three authors compensated the smaller central canon.

44However, when we look at the global graph, the density falls dramatically, to 0,14379. This indicates that some of the literature used in the empire was left out in the republic, but, to a certain point, is expected. Unidirectional acyclical graphs such as bibliometric ones have this tendency. In this kind of graph, previous nodes can not create an edge with newer ones – in concrete terms, an older book cannot cite a newer one. Therefore, when we introduce new chunks of literature published after the initial handbooks were written, the density falls naturally. Therefore, we should compare only graphs comprising similar time frames such as the republican and the imperial ones.

45Cosmopolitanism is the most vigorous trait of Brazilian administrative law. Restrained by the limited number of books available31, the first administrative law scholars looked up to France, which had a similar system centered in the Council of State and marked by the division between administrative and judicial justice systems – the so-called “French model”. And though administrative law usually is presented as a legalistic field, the lack of systematicity of a recently-developed field prompted scholars to rely more on doctrine32, especially the foreign one33. But even as time passed by and the size of Brazilian literature grew, citations of foreign authors outnumbered those of Brazilians. This signals not only reliance on comparative reasoning, but the need to enhance the arguments with the prestige of foreign solutions34. At a deeper level, it is not hard to see that the elite and their lawyers deeply valued mostly European solutions and saw the old continent and sometimes the United States as the benchmarks for civilization and development35.

46Textbooks provide the framework of what was solid and acceptable in mainstream scholarship. But science is also made of discovery, insecurity, and innovation. And especially in law, there is a distance between the scholarly elaboration of systematic abstractions and the daily practices meant for concrete application: legal science is made both of theoretical speculations and the very palpable quest for case-by-case decision. The mediation between these two dimensions is an essential ingredient of legal literature. Moving to the next section, we will dive into this dynamic and concrete part of legal scholarship.

3 – One cosmopolitan journey in two phases: nationality of authors cited in texts on expropriation from law journals

47Law journals are important crossroads where the legal culture is born and disseminated. In the 19th century, even in a nationalist environment, they allowed communication with foreign legal cultures (PETIT, 2006). Moreover, they provided for lawyers privileged access to legal sources such as statutory law, decrees, and court decisions. In the absence of “official publications”, the “limitations of the concrete conditions of dissemination of printed material imposed upon periodicals the duty to be a complete collection, a vademecum” (SOUZA, 2018, pp. 250-251). For the lawyers of the past, law reviews were a refreshing window to a wider legal culture; for the contemporary historian, they provide privileged access to the mental universe of the late 19th and early 20th century. More than that, these sources allow access to a much larger number of texts, making it possible to grasp how numerous authors thought and wrote. This sample can therefore yield a much more representative view of the mainstream thought than the ten jurists who wrote administrative law textbooks.

48Nonetheless, law journals are limited by some methodological hindrances. As Mariana Silveira (2014) notices, the first Brazilian law reviews appeared in the 1840s, still as short-lived initiatives published in economic formats and with few pages. As time went by, editorial businesses became more consistent, and by the end of the nineteenth century, there were already sufficiently consolidated journals36. Notwithstanding that, a large part of the periodicals published in the early 20th century did not last long37.

49For this study, I took the sample from the Library of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais Law School, one of the oldest in Brazil and with an important collection starting from the late 19th century. In an in-person visit to the library, I identified 12 law journals38 edited before 1930. Some were short-lived and unstable, but a few were long-standing publications, which allowed steady editorial practices to be developed. The first example – and also the oldest journal in the sample is – O Direito, which regularly published 120 editions between 1873 and 1913. Other relevant initiatives were Revista dos Tribunais and Revista Forense. It would be impossible to scrutinize every single text published over more than seven decades: I had to choose which ones to look into. I selected all texts in all editions that dealt with expropriation (desapropriação), an institution of Brazilian law that allows the State to forcibly acquire private property in exchange for an indemnity39. Why expropriation? This institute is at the intersection of several legal disciplines: it is closely related to constitutional law, as it interferes in the fundamental right to private property; it is connected with civil law, for it is one of the ways to lose and acquire property; it is linked to civil procedure, as its regulations mostly deal with procedural matters. Therefore, it provides a comprehensive overview not of an isolated administrative law, but also of its borders. Such characteristics are shared with textbooks, which must deal both with internal problems and borderline issues, allowing comparisons. The two samples I am working on within this paper can thus be fruitfully compared; as we shall see in the following pages, the results I achieved with the different parts of the analysis are in line with each other, suggesting they reveal common phenomena.

50The search for expropriation in the indexes of journals has returned a total of 453 texts of court rulings (jurisprudência) and 42 texts of doctrine (doutrina).

51Most law journals included a section called Jurisprudência (court rulings), which tended to cover the majority of pages. These texts belong to different genres, such as final decisions - sentences - and intermediary decisions - responses to appeals, for example. Some texts contain a single decision – from the Supremo Tribunal Federal (Supreme Federal Court - STF)40, for example - while others cover larger fragments of lawsuits, with initial decisions and results of appeals at higher levels of the judiciary. First-level decisions hardly appear though they are not absent. In addition, in 32 cases, the journal was not limited to judicial decisions but published other elements of the lawsuit, such as opinions, petitions, appeals, etc. These texts were grouped separately under the label "procedural records". There is an important methodological reason for this division: the so-called procedural records are written by attorneys and prosecutors, meaning that the specific writing practices they adopt illustrate the mental universe of another category of agents, with professional perspectives and institutional commitments quite different from those of judges. Moreover, the writing patterns to which they were subjected were equally diverse, which led to some specific characteristics of the texts, as we shall see below. Texts classified as doctrine correspond to theorizations on a particular subject from an abstract point of view. Most of them can be called legal opinions (pareceres) – the solution given by an attorney to a specific doubt that normally concerns one specific case. Sometimes, a single question was published with several opinions from different jurists, and, in some high-profile cases, different journals could publish texts on the same case. The famous expropriation of the São Paulo Northern Railroad Company41, for example, stimulated the publication of many of these collections of legal opinions at the beginning of the 1920s. In addition to this kind of text, there were some doctrinal texts that could be called articles - reflections on a limited and abstract theme, with no direct relation to a single case. But this type of text was much less usual. Despite legal opinions being originally devised for a specific case, they were usually presented in the law journals deprived of their context and connections with concrete reality: they were turned into abstract speculation. Therefore, the common characteristic of texts of doctrine is their detachment from concrete legal practice.

52I counted citations in the same way as in the previous section: that is, not once per work, but once for each time the text is mentioned, so, I may compare the two sets of data (administrative law textbooks and expropriation texts). This choice entails methodological issues that must be addressed. The first problem is: what constitutes a single citation? I rarely found footnotes, which would make it quite easy to define what constitutes a unique mention to another text. Instead, most texts paraphrase the authors and mention their names, either in a special form (bold or, more often, italics). Frequently, the writer mentions an author and then abandons his ideas for independent speculation, only to go back to the same work he was discussing before. Shall we count such cases as one single citation or as many as the times the author starts to discuss another text? I addressed the problem contextually: whenever the two mentions to another text are separated only by a few bridging sentences that simply follow the author's reasoning, I registered a single citation; conversely, when mentions are separated by any sort of reference to another text, or the author inserts many ideas of his own, I registered each mention as a single, independent citation. At a more theoretical level, when data for the different texts being analyzed is aggregated, this approach can wrongly inflate the number of citations of a certain author due to the idiosyncratic preferences of a few writers, and not to a more widespread inclination of the scholarly field. The method I choose registers in the same way, in terms of numbers of citations, a work cited several times in a single text, and a text cited only once in several works. This issue would be solved by considering only one mention per work that appears in each text - in the same way as in bibliographic references, for example. But an objection could be raised: that a work that has given extensive basis to a particular text and has been cited by it extensively will be computed with the same value as another work that is simply remembered en passant as secondary support of a hypothesis in many different texts. For this study, I thought that the advantages of the first method outweighed those of the second. Moreover, in the sample I collected, many texts do not cite any other, so it becomes more important to take advantage of the texts that actually engage with a broader textual network, and measure the relative importance of citations in each one of them. Also, the sample size allows us to dilute possible distortions42.

53Now that the conditions and limits of the dataset were exposed, we shall dissect the results. First, I look into the nationality of the authors cited, enabling us not only to compare with the textbooks discussed in the previous section but also to understand the same problems deeper. The country of origin was identified with the aid of encyclopedias, biographical repertoires or, when they were unavailable, combining the language in which the work was written, the place of publication, and other circumstantial information I was able to recover; the information was obtained from the metadata of the work available in a series of library search engines43. The first graphic analyzes the nationalities of authors in the whole period, while the second one displays the number of citations according to the nationalities of authors distributed in periods of 5 years.

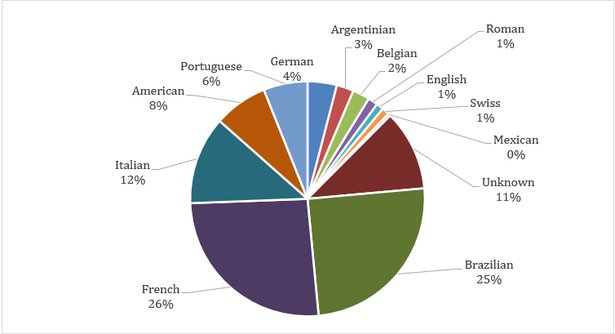

54 Chart 2 Nationalities of Authors Cited in Brazilian Texts on Expropriation (1873-1930)

Chart 2 Nationalities of Authors Cited in Brazilian Texts on Expropriation (1873-1930)

55 Chart 3 Proportion of Citations by Nationality of the Authors cited in Brazilian Texts on Expropriation published in Law Journals (1873-1930)

Chart 3 Proportion of Citations by Nationality of the Authors cited in Brazilian Texts on Expropriation published in Law Journals (1873-1930)

56Once more, we can see the astounding importance of foreign writers: only a quarter of authors cited in the literature on expropriation were Brazilians, as we can see in chart 2. The French were cited at a slightly higher frequency. Chart 3, on the other hand, provides the temporal dynamics of citations. And, it shows a clear break. Two distinct periods emerged: one from the five-year interval of 1873-1877 to 1893-189744, which I call „formative era“, and a second one from 1898-1902 onwards, which I name „consolidation era“.

57Those two time frames express different periods both in the literary practices of Brazilian administrative law scholars and on the underlying structure of the Brazilian state. In the formative era, the public power was still tepid; after the herculean cobstruction of thr order (MATTOS, 2017) from the 1830s to the 1850s, the Brazilian state was not anymore fighting for its own existence against fragmentation; however, its structure was still concentrated in Rio de Janeiro and struggled to intervene effectively in the most distant parts of the territory (SEELAENDER, 2021, p. 165-167). Administrative law, introduced in Brazilian legal curriculums in 1854, would then mostly serve to legitimate and build the state apparatus, differently from the European context, in which it had to cope with changes in legitimacy of an already existing apparatus (GUANDALINI, 2019). By the end of the 19th century, however, significant changes were underway. Industrialization was gaining pace and, at least in the most important urban centers, transport, planning and commerce were calling for further State intervention45. Correspondingly, the doctrine of administrative law became much more concerned with public services and State intervention (SEELAENDER, 2021), though some dissenting voices were still wary of the new works of the Leviathan (SEELAENDER, 2020). The new concept of administrative law was caught in a transition between the liberal order and the new, active state (GUANDALINI; TEIXEIRA 2021). Also, 1889-1891, the political regime of Brazil was changed from a monarchy to a republic, and the administrative jurisdiction (contencioso administrative46) was extingushed, while a federal judiciary was created following the American model47. All of those changes prepared the ground for a metamorphosis: Brazilian administrative law overcame its previous state as a second-tier discipline and went to the forefront of some of the most momentous debates that must be made in the painful moments of the birth of a modern state. These different natures of the discipline would reflect in which countries administrative lawyers would deem more worth looking at.

58In the formative era, the more common authors were Portuguese and French making at least two-thirds of citations in all five-year frames. Brazilians almost never overcome the 15% mark. This changed right before the turn of the 20th century when the consolidation era began. Brazilians took the lead and from 1898-1902 on, they never received less than one-third of citations. France was still the most important foreign legal culture but started oscillating from first to second place among non-Brazilians. Two important new actors surfaced: Italy and the United States. The former was firmly established as the second most important foreign legal culture and even took the lead from the French in 1918-1922. The latter usually alternated with Portugal the 4th and 3rd places. Germany steadily remained in the 5th position, and after that, one could find an indistinct mass of citations of Belgian, Argentinian, English, and Swiss authors, and even jurists from ancient Rome or a solitary Mexican scholar.

59This image of citation practices is mostly in harmony with the one described for textbooks in the previous section. In both samples, we can see two stages: the first corresponds mostly to the 19th century, in which French citations predominate, while in the second phase, mostly equivalent to the 20th century (until 1930), the Brazilian authors take the lead, though with a simple plurality. There is one palpable difference though between textbooks and law journals: texts in the former category cite a larger variety of nationalities (19 against 12), which is probably explained such academic works being longer, having theoretical aims, and needing to display erudition and knowledge of the field.

60How can we explain the pattern we just described? First, we have a French-Portuguese prevalence until 1893-1897, followed by a varying sequence roughly corresponding to 40% of Brazilian citations trailed by French, Italians, Americans or Portuguese, Germans and others, in this order: what explains the difference between the formation era and the consolidation era?

61First, we must establish differences in the datasets of the two periods that might hinder the conclusions. For the “formative era”, we have much less information regarding both the number of citations (only 300 out of 1200) and the number of texts (48 out of almost 500). One could argue that this discrepancy might have distorted the comparison and hampered the results. I believe this is not the case, though: the pattern from the textbooks was repeated in the law journals, suggesting we should interpret our results not as resulting from distorted samples, but from underlying historical phenomena. Moreover, the outcome of this analysis is in line with the context described by the historiography of late 19th and early 20th century Brazil.

62First, we shall comprehend the position of Portuguese authors. Most of the jurists remembered in the Brazilian texts are scholars of civil procedure - namely, Joaquim José Caetano Pereira e Souza and Manoel de Almeida e Souza, a.k.a. Lobão. These two authors, along with Corrêa Telles (also widely cited in our sample), are considered by Lima Lopes (2017, pp. 112-113) as the main references of Brazilian nineteenth-century procedure law. Why? In the absence of a national code of civil procedure, the law in force was the Ordenações Filipinas, a Portuguese compilation from 1603; their most prestigious commentators were precisely from Portugal. Also, according to Lima Lopes, though the first Brazilian books on civil procedure were published only after 1850, the works of both Pereira e Souza and Corrêa Telles were adapted to Brazilian practice by Teixeira de Freitas, one of the most highly regarded imperial jurists. Mostly through footnotes explaining the differences between Portuguese and Brazilian practices, he allowed the jurists of the former metropolis to remain relevant for years to come in the newly independent tropical Empire. However, when the Brazilian republic was installed, procedural law fell under the responsibility of the federated states, leading to the formulation of the first codes; the federal judiciary also got a special law on 11 October 1890. Even if some states48 took a long time to create their codes – São Paulo, for instance, only did so in 1927 - the Portuguese legislation became progressively less relevant.

63Previous research on citations in the Brazilian legal culture suggests this hypothesis is correct. Other historians have shown that Portuguese lawyers were frequently mentioned in texts dealing with civil law. This appeared, for instance, when Mariana Armond Dias Paes (2014, p. 26) examined actions on the legal status of slaves. Staut Júnior (2016, pp. 195-196) found that Portuguese authors comprised more than a quarter of citations in trials on possession (posse) by the end of the 19th century. Sônia Regina Oliveira (2011, pp. 88 ss), researching doctrinal texts of civil law published by the journal O Direito (1873-1889), noticed that Portuguese authors were more cited than all the other foreigners combined or even Brazilians. Actually, the data presented in the previous section shows that the Portuguese are almost absent from administrative law textbooks – a genre in which procedural discussions hardly appear. In other words, at least for the 19th century, wherever there was a process, the Portuguese can be found; in its absence, the former colonizers disappear.

64The increasing references to American authors are easier to explain: the first Brazilian republican constitution (1891) was heavily inspired by the American one49, especially regarding federalism, judicial review, and structure of the judicial branch. Brazilian scholars naturally studied USA authors searching for explanations of some aspects of the constitution; among them, we can find Ruy Barbosa, one of the main crafters of that same constitution. Notwithstanding that, I could find a few citations of case-law on expropriation50 and theoretical works on eminent domain51, though no more than four. Constitutional law was certainly the driving force behind the reception of North American law in Brazil. Procedural law might have felt similar effects, since the decree 848 of 11 October 1890, creating the federal judiciary in Brazil, established that the legislation of the civilized nations would be subsidiary to the Brazilian ones in the federal process, and granted a special place for North American laws52.

65The strength of the French, on the other hand, can be traced to the prestige of their administrative law53 and culture. The “French model” of an administrative jurisdiction separated from the traditional judiciary was adopted in Brazil until 1889, which meant that Brazilian lawyers draw much from French authors – a phenomenon also observed in 19th century Portugal (MARQUES, 1990), Spain (NEIRA, 2005) and pre-unification Italy (MANNORI, 1990). In Belgium, uses of authors and even laws from the larger neighbor were so pervasive that some even said that Brussels had failed to create an independent legal tradition for most of the 19th century (HEIRBAUT, 2000); sharing a prestigious language was paramount to sediment this change, something that appears even more true as one notices that Dutch scholarship was seldom cited in Belgium (MARTYN, 2010, p. 167). But this penchant for France was not restricted to Europe. The French language was widely known among Brazilians and mandatory for admission in law schools54, and the Code Napoleon made a lasting impression on Brazilian jurists. France developed a strong cultural diplomacy in the first half of the 19th century; the French language had international relevance; and the Latin American countries, as they broke with their colonial bonds inherited from the Ancien Regime, looked up to the French Revolution as a model for overcoming the past political model; all of these factors ensured a continuous Francophilia of Latin-American elites even after the French defeat in 1871 (SOLEIL, 2014, pp. 309-380), at least until after the First World War (ROLLAND, 2008). Either as a model to inspire or a counter-model to be criticized, Brazilian lawyers constantly had to face the looming shadow of French law and doctrine in their writings.

66 Moreover, administrative law was born precisely in France, which compelled Brazilians to see this European country’s tradition as stronger and more consistent. Vicente do Rego titled the first edition of the first Brazilian book of administrative law “Elements of Brazilian administrative law compared with French administrative law according to the method of Pradier-Fodéré”: he “took as a model the French administrative law, because it is mainly from the French books that we can now take the principles of our administrative law” (REGO, 1857, p. II). When Veiga Cabral, the author of the second Brazilian book on administrative law, listed the bases from which he intended to build from the ground up the Brazilian doctrine of administrative law, he mentioned fifteen authors that had created administrative law, wrote on institutions similar to the Brazilian ones, or were relevant regardless of their differences from national institutions. All fifteen books were written in French55. For the first Brazilian legal scholarship, “French administrative law is the most complete and developed” (VISCONDE DO URUGUAY, 1862, p. IX). A similar attitude can be found for Portugal during the same period (MARQUES, 1990, p. 245-246).

67Other examples can follow. The book Elementos de Direito Politico (Elements of Political Law), from Louis-Antoine Macarel, one of the founders of French administrative law, even got a Brazilian translation as early as 1842 (MACAREL, 1842). Genuíno Capistrano (1883) used French authors to explain the Brazilian law of expropriation, claiming that, as the two legislations were almost equal, he could use French books. Finally, French scholars sustained in Europe for most of the 19th century a cultural project to export their administrative law: many professors gave lectures in other European countries, and the French had a deeply chauvinistic view of their own administrative law (NEYRAT, 2016, pp. 93-115; 141-195). This even prompted the county’s public law distance itself from the emerging discipline of comparative law (RICHARD, 2017a, p. 20).

68Many other authors that research the international connections of the Brazilian legal culture in the late 19th and early 20th century have also found a French prominence. Dealing with citations of chapters on political crimes in six Brazilian criminal law books of the First Republic (1889-1930), Raquel Sirotti (2017) found that French (37%) and Italian (22%) authors predominated, followed by Brazilians (21%); the exceptional number of Italians is probably explained by the wide circulation of ideas from the Italian positive school in this period56. The prestige of French legal culture was no Brazilian singularity: Prune Decoux (2019) has found that USA scholars frequently used French authors between 1870 and 1940; administrative law as a particularly visited area (DECOUX, 2019, pp. 323-332).

69Beyond general cultural attitudes, concrete circumstances might have contributed to such reception being so easy. Vivian Ayres (2019, p. 105) found that among the authors of books she found in inventories in the city of São Paulo, 46% were French. Maria Garciete Pinto Carneiro (2007, p. 71) found that 43% of the books read between 1900 and 1918 in the Library of the São Paulo Law School were in French – which excludes translated French books. Rio de Janeiro had in the 19th century a bookstore from the French publisher Garnier57. The literary life of 19th century São Paulo mostly revolved around the Law School, as their students and professors were almost the sole audiences for books58. This market was dominated from 1859 onwards by the library of Anatole Louis Garroux, a Frenchman that made a fortune intermediating the selling of French books in Brazil. In 1866, of the 1058 works in his catalogue, 860 (81,3%) were written in French: though São was a small, provincial city, their inhabitants could not complain about its book market (LIBRAIRIE FRANÇAISE, 1866). In the early years of his enterprise, Garroux had a partner, De Lailhacar, established in Recife, the seat of the other Brazilian law school – which might partly explain the overwhelming presence of French authors. But only partly. Nobody would open a “French library” in such a small city as São Paulo if there was not a previous, widespread interest in French culture. Therefore, we can postulate that a two-way process was underway: French authors were praised, stimulating the commerce of their books; as French prints were available and could be easily accessed, for Brazilians to read them, improving their prestige.

70As for Germany, the lack of references can be attributed to the linguistic barrier: the most cited author - Otto Meyer, who accounts for 20 out of the 36 references to the country - is precisely the one whose books had French translations circulating in Brazil. Actually, most citations of Germans refer to French translations. This phenomenon is similar to the reception of Savigny in 19th-century Brazil: he was almost always cited in French, and the absence of a translated version of the Von Beruf prevented Teixeira de Freitas, the most sophisticated Savigny reader in Brazil, from using that book in his discussions of codification (REIS, 2015). Also, France had deep cultural ties with Germany, and some French journals had a wealth of information on German administrative law, even before the unification in 187159; this might have provided a path for Brazilians to get in touch with German scholarship. Other nations sharing cultural similarities with the Germans used more frequently their administrative law – for example, the Dutch (JONG, 1990); if Brazilians had a Germanic language as their native tongue, perhaps Nordic administrative laws would have been more visited.

71The importance of Italy from the 1900s onwards is harder to explain. It cannot be attributed to the late unification of the country, since it had already taken place precisely when the first Brazilian books were written, in the 1860s. Linguistic proximity cannot be an explanation either, because the Spanish-speaking world, with a language much more similar to Portuguese, had far fewer citations than Italy. Viveiros de Castro (1914, pp. X-XI) provides some clues for the simultaneous growth of both Italians and Germans. According to him, the late unification slowed the development of the German science of administrative law, but when it achieved more complexity, they were the first to give autonomy to the science of administration from administrative law60. Clóvis Beviláqua (1902, p. 131), also stated that the Germans and Italians were the main responsible for this development: „the science of administration was systemized by Stein and mostly developed by the so-called, cathedren socialisten Wagner, Engel, Brentano, Lohn, etc., and, in Italy, by Messedaglia, Morpurgo, Ferraris, and others“. This new field, concerned with the social and economic conditions of the administrative reality, was enthusiastically adopted by the Italians in the late 1870s and early 1880s. At the same time, the autonomy between the two approaches lead to a more refined use of the legal method (Metodo Giuridico) in administrative law, enhancing the position of the Italian61 and German scholarship in a more general perspective, and not only in Brazil – Portuguese scholars too started to refer more to authors from those two nations from the end of the 19th century onwards (MESTRE, 1990, p. 250-252). We can therefore hypothesize that this new direction of studies seduced the minds of Brazilian scholars, that started giving more attention to both Germans and Italians. Novelty can be enticing. Spain is almost completely absent from our sample. This could be explained by the phase that administrative law was going through in this Iberian country, mostly dedicated to importing foreign doctrines than creating new ones (NEYRAT, 2016, pp. 210-214). Moreover, the cultural identity of Spanish administrative law scholars has mostly been since the 19th century based on methodological syncretism and an openness to the outside world and on the importation of foreign models – first, the French in the early 19th century, and also Germans and Italians from the late 19th century onwards (NEYRAT, 2016, p. 115-135). A pattern was quite similar to the Brazilian one.

72Finally, we should notice the near-complete absence of Latin American scholars. This was a surprise for me, as the historiography has already stressed the many common initiatives between Argentinian and Brazilian lawyers in the early 20th century, including translations, congresses, visits, etc. (SILVEIRA, 2018). Existing research has shown that Brazilians used their Argentinian counterparts either in books of constitutional law (ABÁSOLO, 2015a) or in the debates of constitutional assemblies (ABÁSOLO, 2015b) and that some North American constitutional theories were mediated by their reception in Argentina (LYNCH, 2012). And a very traditional approach sustains that the exchanges between the Argentinian Vélez Sarsfield and the Brazilian Teixeira de Freitas on civil codification in late 19th century had cemented a Latin American original tradition (WALD, 2004)62. Perhaps the most significant contacts were restricted to Constitutional and Private Law, but, at this point, this is simply speculation. Moreover, in many countries, the doctrine of administrative law entered the 20th century gravely underdeveloped. Some nations followed a pattern of a first early book being published in the 19th century, followed by a long hiatus until new, sparse literature appeared, and a next phase only in the early 20th century when publications gained traction. That was the case in Argentina: until the 1920s, no more than three textbooks dealing exclusively with the field had been published, and only in 1894 a chair separated from constitutional law was created for the area (COUSELO, 1979). This could be at least partly related to the thorough reception in Buenos Aires of American legal culture, which was perceived in the 19th century as being hostile to the very idea of administrative law (ZIMMERMAN, 2019, p. 2 ss.). Colombia was no better: its first book of administrative law was published only in 1895 (PINZÓN, 2019, pp. 276-290). In Chile, the first book was published in 1859, but the next two only went to the presses in 1907; the first chair of administrative law was created in 1888 (BAUZÁ, 2009, p. 83-100). In Mexico, a first book came in 1852, followed by others in 1874 and 1895 (RODRIGUEZ, 2016, p. 311). In general, Latin American nations had much less scholarship than Brazil. Yet, those books existed; it is needed further research to understand if they circulated in Brazil and, if they reached the Empire, why they were ignored by Brazilians. For now, we can say that Brazilian administrative law took little from its Hispanic neighbors. Brazilian administrative law scholars had their eyes - and, sometimes, feet - mostly on Europe.

73The Viscount of Uruguay (1862, p. III), for instance, expressed that one of the reasons why he wrote his book was the impression left on him by the success of French and English administration in his last visit to Europe. Another revealing example is the reviews of the first edition of his book presented by Viveiros de Castro on the preface to the second edition. After quoting a few Brazilian texts, he references two foreign reviewers. The first one is “Letelier, the great Chilean publicist, one of the only South American writers being cited in Europe” (VIVEIROS DE CASTRO, 1914, p. XVIII); that is to say, the criterium used to measure the quality of a Latin American jurist is his value in Europe. The other foreign reviewer was the Spanish scholar Adolfo Posada, who complimented the fact that “Dr. Viveiros de Castro demonstrate a significant knowledge of the modern political-administrative literature (…) from the French school, as Vivien, Batbie, Ducrocq, to the German school, like Stein, Laband, Meyer, Loaning, and the Italian, as Pérsico, Meucci, Orlando, not forgetting the Spanish writers” (VIVEIROS DE CASTRO, 1914, pp. XVII-XVIII). The underlying assumption is that the administrative literature consists in the first place of French, Italians, and Germans, and then of Spaniards. From this perspective, the world outside Europe seems irrelevant.

74From the very beginning, some scholars noticed the excessive fondness of Brazilians for foreign models. The Viscount of Uruguay (1862, p. VIII), for instance, lamented the “lovelessness with which we treat what is ours, not studying it only to superficially read and cite alien things, despising the experience revealed in the opinions of our statesmen”. Antônio Joaquim Ribas (1866, p. VII-VIII) also deplored the dangers of using foreign theories that might have been devised for laws much different from our own – something that “has been causing grave errors among us”. Though foreign legislation was much useful, it must be approached with due care. The French, for instance, had an excessively centralized State and displayed a dangerous predilection for excessive regulation (VISCONDE DO URUGUAY, 1862, pp. XI-XII). Despite the willingness to build a genuinely Brazilian scholarship, those writers still had to rely heavily on foreign scholars, as the Brazilian academic environment was still deploringly underdeveloped: both Uruguay and Ribas cited French authors heavily.

75Years later, already in the 20th century, Oliveira Santos could be more straightforward. For him, the “French administrative regime, in addition for having many defects for which it has been duly reprimanded, is a much-complicated one and, for it, it cannot be adopted as a model” (OLIVEIRA SANTOS, 1919, p. 31). He preferred the German and Italians precisely for their primacy in the science of administration. When he discussed the property of the state, for instance, Oliveira Santos (1919, p. 198) even declared that “for this topic, our administrative law is much more advanced than the French one”. Despite this criticism, his references are significantly French. France remained as a point of reference: it could not remain unmentioned, even though the citation could be negative.

76European law remained the north of Brazilian administrative law scholars. In his book on comparative law, Clóvis Beviláqua used the theory of Henrique Kenkel, who divided the nations into solar peoples and planetary peoples; the former mostly created new cultural artifacts, while the latter mostly received them. Though planetary nations could modify what reached them and sometimes create new achievements, their most frequent attitude was to copy foreign solutions. For Beviláqua (1897, p.36), “in contemporary law, those occupying a prominent place and projecting light are the French, German and Italian laws, especially in private law, and the English and North-American, mostly relating to public law”. This European-oriented attitude seems to be a more widespread tendency even in 20th century Brazilian. When Oliveira Santos (1919, pp. 246-258) decided to explain the administrative organization of foreign countries, he wrote about thirteen European nations (England, Sweden; Norway; Denmark; Holland; Belgium, France; Spain; Portugal; Germany; Switzerland; Italy; Austria-Hungary) and only two in America (USA and Argentine). In other words, distant Sweden got more attention than the whole Latin American continent. The Brazilians themselves devalued their own culture.

77For many people, the international orientation felt somewhat uncomfortable. Nevertheless, their eyes remained fixed on other countries: the Brazilian educational environment was seen as too underdeveloped to produce a fully original administrative law. The solution was to critically evaluate and import foreign institutes. But almost always from Europe: Latin America never got much attention in the former Portuguese colony. National jurists always had a clear idea of what was the “center” from which they must get inspiration, though a reasoned one: France, in the formation era, and France, Germany, and Italy followed by the USA in the consolidation era.

78Brazilian administrative law was fully pervaded by cosmopolitanism. But a deeply Eurocentric one.

4 – Prominence of one author or value of a whole country? The impact of legal cultures

79How far can we attribute the citations of one country to one or some exceptional authors, who artificially raised the indexes of that jurisdiction? Or are they associated with a more widespread prestige of that particular legal culture? Good answers can be provided by a class of statistical variables called “measures of dispersion”, which we will now apply to the texts on expropriation in law journals .

80One of the most important variables of such type is the standard deviation. It corresponds to the square root of the mean of the square of the distance between the values and the mean. It shows how much the values within a sample are near to the mean. In other words, when the values in the sample are near each other, the standard deviation is low, and, otherwise, when they are too different, the standard deviation is high. Taking into consideration the data above, a low standard deviation for some countries tells us that its authors received a similar number of citations, while a high standard deviation probably shows that few authors received many citations, and most of them received a low amount – or the other way around.

81However, it is difficult to significantly compare standard deviations of different samples when their means are very different - as is the case with the samples under analysis. Hence, another measure was chosen: the coefficient of variation, which is the result of the division between the standard deviation and the mean. It indicates how far the data of a given sample are from the mean. And, in the case under analysis, it allows us to say which countries have authors with a more or less homogeneous number of citations. This is what we can see in the following table, based on the citations found in texts on expropriation taken from law journals:

Nationality | Number of authors | Number of citations | Mean | Standard deviation | Coefficient of variation |

Ancient Roman | 4 | 5 | 1,25 | 0,5 | 0,4 |

American | 22 | 78 | 3,5 | 3,8 | 1,1 |

Argentinian | 7 | 10 | 1,4 | 0,5 | 0,4 |

Belgian | 7 | 20 | 2,9 | 1,7 | 0,6 |

Brazilian | 74 | 385 | 5,2 | 7,8 | 1,5 |

English | 3 | 4 | 1,3 | 0,6 | 0,5 |

French | 77 | 257 | 3,3 | 5,3 | 1,6 |

German | 12 | 36 | 3 | 5,41 | 1,8 |

Italian | 36 | 120 | 3,3 | 4,9 | 1,5 |

Mexican | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - |

Portuguese | 18 | 151 | 8,4 | 16,2 | 1,9 |

Swiss | 3 | 14 | 4,7 | 6,4 | 1,4 |

Unknown | 33 | 52 | 1,6 | 0,9 | 0,6 |

Total | 297 | 1133 | 4,1 | 7,9 | 1,9 |

82The first distinguishable result is the relatively high coefficient of variation of countries such as Germany and Portugal. This suggests that both jurisdictions were not much influential on their own, but only through a small group of authors. For Germany, some of these names are Savigny, Paul Laband, and the aforementioned Otto Meyer. An in-depth analysis of the cited books from each country confirms this interpretation: no Portuguese book of administrative law is cited, even though a Portuguese monography on expropriation was published in 190663. This is a sign that Portugal’s role, though very important, was restricted to certain branches of legal knowledge, as discussed before. Not by chance, this is the nation with the higher mean of citations by author.

83On the other hand, France combines two interesting features: it has the highest number of authors, but also a relatively high coefficient of variation – in fact, slightly higher than the Brazilian one; Brazil, additionally, has third more citations than France. This is evidence that many of the French authors were sparsely cited - they appeared few times, in single mentions. This suggests that many of these citations were simple demonstrations of erudition, without further in-depth analysis. A comparative example of such practices can be taken from the textbooks: some of their authors nurtured the habit of mentioning several foreign jurists in a row as having one given opinion but did not truly engage with their thought64, as previously discussed. More research must be done on the many possible meanings of citations65, but the data I have just presented implies that only a few jurists were constantly employed, having a greater impact on the Brazilian culture. Others were used in a very specific context, frequently in a superficial way. This diversity must be taken into account to assess the international networks of jurists with more precision.

84Americans, on the other hand, have a low coefficient of variation, even though they are not frequently cited (less than 80 times). This is most likely because the most frequent citations are from a small group of authors of constitutional law - that is, those who clarify important axioms that must be applied in expropriation, in particular, if administrative decisions can be submitted to judicial review, but that does not directly impact the solution of the legal problems under discussion. Therefore, Brazilian authors used a restricted bulk of American scholars in many texts. The use of USA books on expropriation is rare. This implies, so to speak, a "diffuse Americanism" in many texts: a specific use of North American authors that do not deeply structure the reasoning.

85Another interesting way to investigate the dispersion of quotations is the h-index – a widely used metric in contemporary scientometrics. This number corresponds to the n-amount of texts or, in this case, authors, who have at least the same number n of citations66. For instance, if one country has 7 authors that were cited respectively 37, 18, 13, 4, 3, 3, and 2 times, its h-index will be four, as it has four authors with at least four citations. The h-index is usually used to measure the academic productivity of individuals, but it is also constantly employed to assess the production of groups of people, such as countries67. This metric has one crucial advantage over the mean: it returns low values for groups that have high concentrations of citations, as it is the case of Portugal. But it also clarifies aspects that are not covered by the coefficient of variation: the h-index returns low values for samples that, although quite homogeneous, are seldom cited; this allows us not only to understand which legal cultures were more homogenously cited but also those more significant for Brazilian scholars. Let us see the results:

Nationality | h-index |

Ancient Roman | 1 |

American | 6 |

Argentinian | 2 |

Belgian | 3 |

Brazilian | 11 |

English | 1 |

French | 7 |

German | 3 |

Italian | 5 |

Mexican | 1 |

Portuguese | 5 |

Swiss | 1 |

Unknown | 3 |

Total | 14 |

86This table shows, for example, that eleven Brazilian jurists in our sample were cited at least eleven times, or that five Italians were cited at least five times. Comparing this table with the previous one, it is possible to see that, although Switzerland has its coefficient of variation among the lowest, which means homogeneity among its authors, it also has a very low h-index: only 1. This means that only one of its authors was cited more than once68. Swiss jurists were therefore homogenously low cited by Brazilians. Something different happened with Americans and Portuguese scholars. The distribution of the former is particularly homogeneous, but that of the latter is especially concentrated, yet their h-indexes are similar: 6 for the USA and 5 for Portugal. This means that both countries had a fair number of relevant jurists, but Portugal, differently from the USA, also had several low-key scholars only sparsely mentioned, leading to a higher coefficient of variation. In addition, the h-index shows that the number of relevant Brazilian authors is higher than that of French ones since the h-index of Brazil is 11, well above the 7 achieved by France, though both coefficients of variations are almost equal. This means that both countries had a similar dispersion in the citation of authors, though the central French authors were less cited than the most important Brazilian jurists.

87The joint analysis of the h-index and the coefficient of variation, coupled with a qualitative observation of the works, reveals some trends. First, a generic prestige attributed to France, with the side effect that some authors were presumably used in a superficial way. Second, a few Portuguese authors are highly regarded, though this prestige is concentrated in a restricted group of authors. Third, the USA is seen as important, but within the narrow scope of constitutional law, and without excessive emphasis on a particular author. Fourth, Italians are close to the average, without any special characteristics, in terms of the mean of citations, the coefficient of variation, and the h-index.