1At first glance, the English logging settlements that sprang up between Chetumal Bay and the Mosquito Shore from the mid-seventeenth century seem extremely insignificant. For most of their history, they contained just a few thousand free people and slaves. Some of the settlers who harvested wood in the Yucatan from 1630 traced their logging rights dubiously to the failed colony at Providence Island. Many loggers on Miskitu land were descended from privateer/pirates who, from 1765, had seized land and harassed Spanish ships, mostly without British permission.1 They all made a living harvesting and exporting mahogany and logwood. Yet, I argue here that their very precarity makes them worthy of closer examination.

2In doing so, I add to a growing strand of legal history that insists that the very idea of sovereignty was constructed and unraveled on the edges of Empire. This work starts with foundational scholarship by Lauren Benton and others on the inconsistent, variable and speculative adaptations of public and private Roman-law to ground claims of authority and possession (imperium and dominium) in the course of European expansion.2Benton’s A Search for Sovereignty in particular showed how consequentially uneven claims of sovereignty were crafted to fit different colonial geographies.3Law and Colonial Cultures argued that claims and counterclaims in the margins of empire worked both to constrain and extend the reach of colonial legal regimes from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries.4 My own work suggests that contests about the legal status of indigenous people in Anglophone settler polities demonstrate the fluidity of sovereignty claims and jurisdictional practices well into the nineteenth century, and, indeed that they hardened in the encounter between settler criminal law and Indigenous people.5 Inge Van Hulle’s Britain and International Law in West Africa explains the continuation of legal creativity in the search for authority to expand commerce and empire in African from the mid-nineteenth century.6

3Here I explore how the reconstituted British logging settlement at Belize emerged as a curious incubator of sovereignty talk among British administrators and local magistrates. Though there has been a recent renewal of interest in claims made by Britain to the region in the law of nations to 1790, this piece focuses on how the peculiar Anglo-Spanish treaties of the late eighteenth century provoked prolonged, unexpected and deep inquiry among British administrators and loggers into the nature of sovereignty, and its relationships to territory, subjecthood and jurisdiction.7 Here I explore this entanglement in multiple registers, through interpretations of the treaties by British lawyers and administrators, and through the intimate ramifications of their musings for everyday order in what became British Honduras.

Context

4The English logging settlements formed on the eastern shores of the Spanish mainland from modern day Belize to northern Nicaragua were the subject of increasing debate from the late seventeenth-century. This was so because Spain claimed the swamps and forests that the settlers harvested for logwood and mahogany, and their wares formed part of a thriving trade of disputed legality between British, Spanish, Dutch, French and other colonists in the Caribbean – a multilayered entanglement.8 Yet Britain did not aspire to govern these places at all until the mid-eighteenth century, and the settlement at Belize did not become a colony until 1862. Until then, these were not formalised settlements with letters patent and governors. For much of their early history, they were self-forming and contingent places. As a result, everything about these settlements and their occupants was ambiguous. But ambiguity was not the same as invisibility.

5These tiny settlements were not invisible in part because the logwood trade was vital for dying fabric and various Governors of Jamaica, among others, saw an opportunity for England to control its harvesting and distribution. Loggers also engaged in depredations as well as illicit trade and, “from at least 1699”, they used the cover of inter-imperial war to justify raiding and stealing from Spanish settlements.9 Settlers on the Mosquito Shore allied with Miskitu Indians who hated the Spanish more than the settlers, even though the latter occupied their land and had enslaved some of their people. To the north in Belize, the Captain Generals of Yucatan lamented that they could not mobilise Mayans to expel loggers on their behalf. At various times, and with varying success Spanish officers managed to attack and destroy some logging settlements, but they seldom had the manpower or will to establish effective control of the region. This was so in part because the settlements spanned two Captaincy Generals, but it was also because the Spanish Empire was stretched so thin.10 So, competing claims and violence on the ground became the object of increasingly testy international agreements.

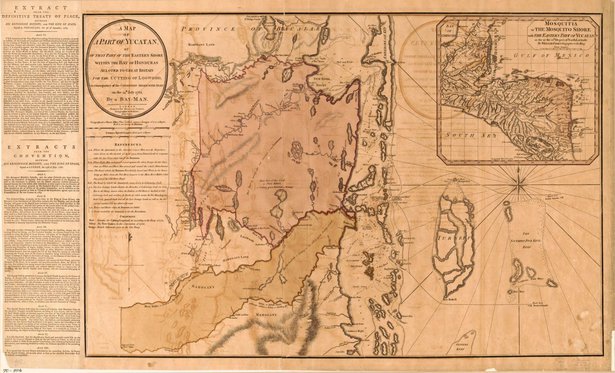

6 Figure 1: William Faden, A map of a part of Yucatan, or of that part of the eastern shore within the Bay of Honduras allotted to Great Britain for the cutting of logwood, in consequence of the Convention signed with Spain on the 14th July 1786. (London, 1787). Library of Congress Geography and Map Division Washington, D.C. 20540-4650 USA dcu; http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g4820.ct008427

Figure 1: William Faden, A map of a part of Yucatan, or of that part of the eastern shore within the Bay of Honduras allotted to Great Britain for the cutting of logwood, in consequence of the Convention signed with Spain on the 14th July 1786. (London, 1787). Library of Congress Geography and Map Division Washington, D.C. 20540-4650 USA dcu; http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g4820.ct008427

Treaties

7Eva Botella-Ordinas has described the earliest English claims to the Belize settlements (in the southern Yucatan province) in the aftermath of the Treaty of Madrid (1670). Article VII of the Treaty of Madrid (1670) provided “That the Most Serene King of Great Britain, His Heirs and Successors, shall have, hold, keep and enjoy forever, with plenary Right of Soveraignty, Dominion, Possession and Propriety all those Lands, Regions, Islands, Colonies and Places whatsoever, being or situated in the WEST-INDIES, or in any Part of AMERICA, which the said King of Great Britain and His Subjects do at present hold and possess.” This term had been deemed sufficient to cede Jamaica to the British, so pundits claimed that Spain had also ceded logging settlements in Belize.11 The result was an impasse: “Spaniards did not consider the English to be holding and possessing territories where the Spanish claimed jurisdiction. The English contested the lands over which Spain claimed jurisdiction by arguing that these lands were not actually settled, planted, and improved by the Spaniard.”12 Botella-Ordinas argues that the debate – which included John Locke – hardened an emerging British ideology of empire predicated on the idea that English improvement should trump Spanish wastage in the New World.13 But the power of this ideology can be overstated, and in any case scarcely applied to the extraction of logwood from the swamps of the southern Yucatan. Though Britain pressured Spain to explicitly cede logging settlements in negotiations leading up to the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, Spain refused.14 It simply confirmed the agreement of 1670.15 Thereafter the British were remarkably (indeed increasingly) restrained in their claims to mainland logging settlements.

8At the same time, Spain became more determined to remove Britons from ‘its’ soil, especially on the Mosquito Shore where British-Miskitu diplomacy posed very real threats to the Spanish settlements. Escalating violence between Spanish and British loggers and traders combined with an increase in Spanish seizures of British ships carrying contraband helped to precipitate the War of Jenkins’s Ear.16 During the war, Britain started to actively harness the various settlements’ predatory inclinations for the purposes of the British Empire.17 In 1740, the Governor of Jamaica was “ordered to send ‘some discreet person’” to take stock of “the Bellise settlement” to the North and he sent Robert Hodgson to mobilise residents and the Miskitu on the Mosquito Shore against the Spanish.18 At the end of the conflict, the British Government officially appointed the first superintendent to govern the settlements, taking over that responsibility from Jamaica.19 Though these makeshift moves fell far short of establishing colonies, from this moment onwards, British loggers seemed to the Spanish to have transformed from pirates and contraband traders into emissaries of British Empire on what Spain considered to be its soil.

9Regional violence and disputes over the settlements were also instrumental in Spain’s entry into the Seven-Years’ war – an outcome Britain had struggled to avoid. For this reason, they were the subject of the most pointed treaty negotiations to date in 1763. In the Treaty of Paris, in return for the Floridas, the British Crown promised, inter alia, to demolish fortifications “which His Subjects shall have erected in the Bay of Honduras, and other Places of the Territory of Spain in that Part of the World.” For its part, Spain would “not permit His Britannick Majesty’s Subjects or their Workmen, to be disturbed, or molested” in their harvesting of Logwood. They would be allowed to “build” and “occupy without Interruption” houses and magazines and be assured “the full Enjoyment of those Advantages, and Powers, on the Spanish Coasts and Territories…”20 This treaty resulted in immediate confusion. Some loggers claimed that they could not be affected by the treaty because they lived on British, not Spanish soil (by right of long and effective occupation and the 1670 treaty). Meanwhile, the Spanish colonial government sent Lieutenant Colonel Díez Navarro to take over governance of the Shore Settlement, where he had to take refuge from angry Shoremen and Miskitu Indians.21

10Loggers also figured in negotiations again after the American Revolutionary Wars. Article VI of The Treaty of Versailles (1783) granted loggers the “right of cutting, loading and carrying away” Logwood in a constrained “District lying between the Rivers Wallis or Bellize, and Rio Hondo” and on the condition that “these Stipulations shall not be considered as derogating in any wise from [Spain’s] Rights of Sovereignty.”22 Loggers in Belize sent a long and angry memorial (supported by the governor of Jamaica) complaining that “the limits of their settlements and privileges assigned to therein” were “most unexpectedly and extremely diminished”: they demanded renegotiation.23 More ominously, in 1783 Britain also promised to remove settlements from all other parts of the “Spanish Continent.” That meant that all of the logging settlements on the Mosquito Shore had to be abandoned. This last concession was made in error. Diplomats had been told that they should give up logging settlements before returning Gibraltar, but they failed to comprehend that they were not really supposed to concede either. When Britain tried to backpedal, negotiations nearly broke down.24

11So, Britain and Spain entered further negotiations and, in 1786, they signed the most remarkable of treaties about the settlements. In return for Britain’s explicit agreement to remove some “2,300 Englishmen and their families and slaves” from the Mosquito Shore “as well as the Continent in general” Spain reaffirmed the right of Englishmen to harvest wood in Belize within boundaries slightly expanded from the 1783 agreement “as well as gathering all the Fruits, or Produce of the Earth, purely natural and uncultivated”. “But,” this fascinating agreement went on to provide, “it is expressly agreed, that this Stipulation is never to be used as a Pretext for establishing in that country and Plantation of Sugar, Coffee, Cacao, or other like Articles, or any Fabrick or Manufacture, by Means of Mills or other Machines whatsoever…”25 Just to be clear, however, the treaty required that occupants of the settlements harvest their wood and fruit “without meditating… the Formation of any System of Government, either military or civil,further than such Regulations as their Britannick and Catholick Majesties may hereafter judge proper to establish, for maintain Peace and good Order amongst their respective Subjects.” British settlers “shall take Care to conform to the Regulations which the Spanish Government shall think proper to establish amongst their own Subjects” in all Anglo-Spanish interactions in the region.26

12Much of this language was fiction: settlers had lived around the Bay for more than a century, and though they harvested wood for trade, they had certainly built houses, bought slaves, grown things and even exercised a semi-independent form of government through elected magistrates, overseen first by Jamaica and increasingly by the Colonial Office. But these treaty-fictions also had legal effect. The settlers could (and had) mounted claims to settlements on the basis of usucapio.27 But Britain promised in 1783 and 1786 not to claim sovereignty through its subjects’ uninterrupted use of land. Its repeated acknowledgements of Spanish sovereignty since 1763 nullified the inter-imperial ramifications of long use in the past and, though Belize settlers went on to cultivate plantations full of plantains, pineapple and watermelons in violation of the treaty, in 1786 Britain promised not to mobilise those activities to make sovereignty claims in the future.28

13Though some scholars and many contemporary maps refer to these agreements as a significant cession of land to the British, they did not create a British colony in Belize. So much is clear from a series of legal opinions and local crises about peace keeping that unfolded in the decades before Mexican independence.

Governing without Sovereignty: The Advocate General’s opinion

14Even after signing the much less prescriptive Treaty of Paris in 1763 – which merely preserved Spanish sovereignty and required the demolition of all British fortifications in “the territory of Spain” without further limitations on governing the loggers – the Board of Trade (a metropolitan body that oversaw Colonial Governance for most of the eighteenth century) was worried about the relationship between sovereignty and everyday peacekeeping in the logging settlements. It wrote urgently to James Marriott, Advocate General, asking whether and how Britain could keep the peace in “the Territory of Spain”? Could “his Majesty… establish any formats of… government or jurisdiction among the British subjects in the Bay of Honduras consistently with the Letter and Spirit of the 17 Article of the Treaty of Paris?”29 The Board’s instinct was that Britain needed some sort of oversight of the settlement. It proposed formalising the office of superintendent created by Jamaica in 1740 “to retain and secure the Affections and Interests of the Indians inhabiting that Shore, and prevent any thing which may tend to disturb the Public Peace.”30

15Marriott was discomforted by the briefing. He claimed to be out of his depth and suggested that the attornies-general or, better still, the drafters of the impenetrable provision should be responsible for unravelling its mysteries. Having pled incompetence, Marriott tried very hard to find grounds for establishing British Government in the settlements in the ambiguous terms of Article 17. The result was the most convoluted legal opinion I have ever found in the archives. As treaties belonged to the Jus Gentium, he reasoned, Article 17’s interpretation must rest on Roman law. For ten pages or so, Marriott wrestled with grammar and almost convinced himself that Britain had not conceded Spanish territorial claims to the logging settlements throughout the region at all in the first part of Article 17. His tortured logic does not bear close scrutiny. Suffice to say it ends in the assertion that, if Britain had renounced claims to the settlements in Article 17, then it had probably also lost Jamaica.31 It came to naught because Marriott had to concede that Britain had specifically agreed that Spain had a superior territorial right to the Bay in the second part of the Article: “his Catholick Majesty assure[d]” certain rights to British subjects in the region, exercising his rights as a territorial sovereign.

16Did the limited “usufructary right” granted to settlers carry with it the right to govern British settlers? Marriott thought it “pretty certain that where no sort or degree of territorial right exists no sort or degree of jurisdiction can be exercised.”32 But he also insisted that a right to harvest and build houses was a mode of territorial right, however partial. This right “carries with it [a] sort of possession, Dominion, and property.” More importantly, by conceding that the residents of the territory remained British Subjects, Spain conceded, in effect, that the residents of Honduras Bay were not subject to its jurisdiction. Rather Article 17 assumed that British Subjects in Honduras still enjoyed the privilege of British protection in their limited rights to live and harvest wood in Honduras. If the Crown of Great Britain was not responsible for keeping order there, then the community would be comprised of outlaws, “subject to no jurisdiction at all” and able to “commit irregularities and outrages on the neighbouring settlements” without check. Such an outcome could not be in the interests of either party.So, he concluded, “it should seem then to result from the whole of these considerations that there is some sort of territorial right in a certain degree [of] a useful and solid nature acquired by Great Britain sufficient to maintain and exercise… civil jurisdiction over its own subjects in the Bay of Honduras.”33 To this end, Marriott thought the king might send both a superintendent and a judge to Honduras.

17Then, he hedged. If the hidden intent of the drafters made his interpretation unworkable, Marriott thought that the Crown might, instead, resort to legal fiction to keep the peace. He suggested that the Crown might “declare and interpret… the several acts done by British subjects residing in the Bay of Honduras… to be understood in law to be as if those acts were done at Jamaica.” As he pointed out, such fictions were “not uncommon in the Law of England”: the Bill of Middlesex had long allowed the King’s Bench to wrest causes from Chancery by declaring them to have been committed in the county of Middlesex, and therefore within its jurisdiction. Jurists from Coke to Hale used a similar device to bring contracts and conflicts involving English interests abroad within the jurisdiction of common law courts.34 But Marriott also admitted that he knew little of diplomacy, and, if Article 17 was anything to go by, it must be a mysterious business indeed.35

18In Marriott’s rendering, in the absence of sovereignty, authority to keep peace in the settlements was suspended somewhere between the barest of territorial claims, the power of a sovereign to regulate his subjects abroad, and legal fiction. But most of this justification fell apart in 1786, when Marriott’s careful parsing was negated by stipulations that there could be no organised government in Honduras, and by the fact that settlers’ rights of user were so much more constrained. Treaty constraints told in disorder.

Governing without Sovereignty: Custom and Order in Practice

19Since the early eighteenth century, the tiny communities of loggers had managed local affairs by electing magistrates to govern and to exercise jurisdiction in defence of the peace. As the century progressed, some, but not all of the Magistrates at Belize were given commissions by the governor of Jamaica.36

20As noted, in 1740 the Jamaican governor had also sent a superintendent to the Bay settlements, a function taken over by the Crown from 1750. The Crown continued to send superintendents after, and in spite of, the late eighteenth-century treaties. After reading Marriott’s verbal gymnastics, in 1763, the nervous Board of Trade sent a superintendent but not a judge to the settlements. In 1763, Joseph Otway was commissioned to “not only to observe the engagements of the late Definitive Treaty, but to prevent any attempt which might tend to disturb the public Peace, whether it should arise, on the One hand, from any irregular Conduct of the Inhabitants, or, on the other, from the Enmity of the Indians to the Spaniard.”37 By 1767, Whitehall was even more judicious. Shelburne commissioned a new superintendent, Robert Hodgson, not to keep the peace, but to apply himself to “doing and performing all… Manner of Things thereunto belonging, And you are to observe and follow such Orders and Directions from Time to Time as you shall receive from Us.”38 Thus began a long tradition of sending superintendents with vague instructions but no clear authority to do anything at all in the settlement except to placate Indigenous Peoples and Spaniards in equal measure. As a result, these superintendencies were chronically dysfunctional: their authority was invariably disputed – sometimes openly defied – by local magistrates.

21The legitimacy of the Belize magistrates was also persistently questioned by loggers, even before the influx of refugees after 1786. So riven was the Belize settlement by disputed claims and contested authority that, in 1765, visiting Admiral Sir William Burnaby drafted a code of laws or mini-constitution for the settlement that recognised the authority of magistrates and regulated the dispensation of logging claims.39 For good measure (clearly anticipating further problems) the Burnaby Code stipulated that the commanding officer of any visiting naval ship could punish malefactors according to the code.40 Nevertheless, a passing Admiral in 1768 noted that “the Bay-men at Honduras have shook off all subjection to the Magistrates.”41 The fragility of public authority made race slavery in the settlement particularly fragile, resulting in multiple slave revolts in the Belize settlement after 1760 and persistent slave desertions (a relatively easy thing to do when slaves worked under minimal supervision in the forests). It is surprising that the settlement survived at all as, in 1779, slaves were reputed to outnumber free settlers by more than 10:1.42 Though the free/slave ratio reduced markedly after the influx of the poorer residents from the Mosquito Shore,43 politics among the free population became more explosive after 1786.

Governing without Sovereignty: An Interracial Riot in 1810

22The problem was that, though the British Government may have made its peace with the tension between its obligations to Spain and the institutions of government in the settlement by sending out poorly instructed superintendents, this compromise dissolved whenever somebody looked at it squarely.44 A series of disorders in the early nineteenth century prompted superintendents, the Secretary for War and the Colonies45 and Crown law officers to do just that.

23One such incident occurred in 1810, when local civilian courts tried to charge a group of black soldiers of the 7th West India Regiment with battery and riot. As usual, as the Napoleonic Wars raged on, the War Office read Britain’s promises to Spain about the logging settlement very loosely. Though the Belize settlement was not technically fortified, it was garrisoned by West India Regiments during the war. The trouble started with a fire in Belize around 9pm on the evening of 4 September. Half the town and a good number of soldiers came to see what was going on. None of the deponents speculated about how the fire started. Archibald Colquhoun (sometime magistrate) deposed that about twenty soldiers, though not dressed in uniform, had their bayonets drawn. They used these to force “every Negro and person of colour belonging to the settlement” towards the fire, presumably to fight it.46 This is not entirely clear because more than one soldier was accused of beating people, like the “apprentice lad” Robert Gladding, even though John Collins swore that Gladding was “engaged in pulling down the ruins.” When Collins went to Gladding’s aid, he and the “lad” were set upon by two privates, Caesar and the drummer Teague.47 John Smith reported seeing a soldier “named Joseph striking Robert Gladding with a stick” until it broke, then drawing his sword. Smith grabbed the sword so that Gladding could escape, and Joseph punched him in the mouth for his trouble.48 Two neighbours – J.B. Everett and George Westby – also claimed to have intervened in Gladding’s defence. Everett attested that a soldier had attempted to hit him with a stick when he entered the fray. He saw Lieutenant Kirk “in a passion” – swiping his sword at passers-by and hitting Collins in the head.49 Other officers, Edward Bennet attested, stood idly by.50

24If the incident began as a racially selective effort (by enslaved soldiers) to mobilise spectators to fight a fire, the good people of Belize thought it ended rather differently. Collins swore that Caesar insisted that “he should go into the fire.”51 Everett swore that the “great number of soldiers” were “very violent” in their efforts to drive “the black and coloured people… towards the fire.”52 Richard Debb said he saw drummers and fifers “with drawn swords running after and beating every black or coloured person they met who came to give assistance at the fire.”53 We get no sense from the records of what made the Black troops attack Black residents. But Debb and Collins both called the incident a “riot”, while Everett thought the incident would have been “very serious”, had not the magistrate Mr Paslow chastised the soldiers and ordered the residents home.54

25Armed with allegations spanning riot and attempted murder, the high constable of Belize waited on Superintendent Smyth with warrants demanding that Caesar, Teague and Lieutenant Kirk be surrendered to the civil power for trial. Smyth refused, promising only to hold a local court martial to investigate allegations made against the soldiers in order to determine whether they should be sent to Jamaica for trial by a general court martial. As the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, the Earl of Liverpool confirmed later, the Mutiny Act and the Articles of War together established the conditions under which soldiers might be tried in places like Honduras. They required that “in the Garrison of Gibraltar in the Island of Malta or in any place wherein there is no form of Civil Judicature in force, the Commanding Officer shall convene Courts Martial for the Trial of Offences committed by the Military under his Command.”55 Accordingly, Smyth said he could not surrender soldiers for trial by the civil courts of Honduras because the convention of 1786 prevented Britain from establishing proper courts there.56

26This claim was legally uncontroversial, but it did not please the Honduras magistrates. They protested that they had always exercised jurisdiction over wayward soldiers and naval men in the settlement. ‘Always’ was a strong word given that the settlement had only been garrisoned sporadically. But they went to the trouble of appending records of incidents since 1797 nevertheless. The most serious of these was the capital conviction of a forger who was also an officer on HMS Merlin. They did not specify in what year. However, the prisoner was reprieved, and the case referred to the Earl of Balcarres, then Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica. The magistrates claimed that Balcarres acknowledged the validity of the proceedings by promptly pardoning the man involved. This was hardly a ringing endorsement of criminal jurisdiction at Belize.57 More recently, in 1809, residents claimed that they had tried three officers of the 7th West India Resident for “assault and outrage”, and a local jury had sentenced them to “certain fines.”58

27The magistrates felt that Smyth’s refusal to surrender the soldiers was “alarming and dangerous”. It reflected an effort to make “the Military paramount to and independent of the civil Authority and has a Manifest tendency to introduce a Military Government amongst us.”59 That military government not only undermined the rights of free British subjects, the race and status of the West India troops threatened local order. The settlement’s agent George Dyer pointed out in 1811 that, “the Soldiers in Honduras are black and that by serving His Majesty they become free.”60 Any soldier’s independence from civil authority was dangerous, but slave soldiers – involved here in terrorizing free black members of the community – encouraged rebellion. Smyth’s challenge to their jurisdiction, then, undermined local racial slavery even as it picked away at the legitimacy of all civil and criminal jurisdiction in the settlement.

28The real significance of the dispute was larger than a few refractory soldier-slaves and a court martial, however. Smyth went on to argue that, “far from having the right to try the Military, the magistrates do not even possess the power of holding criminal Courts for the trial of offences committed by the Settlers”.61 Liverpool was more tactful. He said that the civil inhabitants might by “general convention... submit to the Jurisdiction of a Court not… established” by Parliament or the King, but soldiers could not do so according to existing law.62 Both implied that there was no legitimate civil jurisdiction in Belize at all. The magistrates were outraged. “General convention” was not a strong basis for hanging civilians for capital crimes, as they had done from time to time. Settlers wrote to protest that the jurisdiction of their magistrates had been “withdrawn” leaving them “in a novel and unprecedented State of being the only subjects of Your Majesty who are deprived of… participation in the blessings of that happy constitution under which Your Majesty’s Dominions enjoy protection in their Property and safety in their persons.”63 The absence of sovereignty here destroyed all authority to keep the peace.

Governing with Sovereignty: Transnational Theft and Murder in 1815

29London had clearly hoped that the settlement would continue on as though the 1810 controversy had never occurred. In 1814, incoming superintendent George Arthur was told that “until Circumstances shall admit of a more comprehensive arrangement, the free exercise will be continued to [the magistrates] of the antient Laws, Regulations and Customs in all Cases Criminal and Civil,” so long as they limited their punishment to fines, imprisonment or transportation “out of the settlement.”64 The new Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, the Earl of Bathurst even suggested that Arthur should consult with the magistrates about how best to punish capital crimes committed by or against soldiers in the settlement.65 That time for such obfuscation, however, had passed.

30The residents were more scrupulous than Bathurst, and Smyth’s denial of jurisdiction soon prompted a fresh series of crises about magisterial authority. “Almost immediately on [his] arrival” in July 1814, the magistrates told Arthur that the settlement was in disarray, and their authority so contested that they found it impossible to hold regular sessions. By December, when Arthur wrote home about the state of the settlement, the situation had worsened, “the courthouse is now a constant scene of riots and contention, in which, the public jury, and magistrates are equally violent and disorderly.” 66 “[I]lliterate men of the worst characters,” corrupted by the desire for re-election, presided over all civil and criminal matters in the settlement. Since Arthur’s arrival, under pressure from the mob, they had deliberately maladministered two sizeable deceased estates. One included property bequeathed to the Spanish Captain General. In another, they refused to hand over the management of an estate to the deceased’s spouse for so long that the plantations’ slaves downed their tools and came to town in search of new owners.67 “But”, Arthur continued, “this disgracefulexhibition is harmony itself in comparison with the proceedings of the Public Meetings, which are now conducted with so much animosity & violence by the Lower Class of the Community, that is not difficult to predict the completion of their views in the speedy subversion of every regulation that has been adopted for the happiness, prosperity, and security of the service.”68

31The situation was so dire that Arthur considered declaring martial law on his arrival, though his authority to do so was doubtful to say the least.69 In the same letter, he proposed radically limiting the franchise. He asked the King to decree that only British-born white men worth more than £200 would be eligible to participate in the public meeting. Magistrates would need to be white and hold property worth £1000. All legislation should be passed by a superintendent and the magistrates, under threat of veto by the superintendent in the king’s interest.70 In January 1815, he requested summary power to expel troublemakers (especially foreigners) from the settlement.71 A few weeks later, Arthur urged the Crown to impose restraints on the civil and political rights of all free people of colour.72 These suggestions were mostly ignored because they looked a lot like exercises of sovereignty in foreign territory. However, a marginal note from Bathurst suggested that he approved of bringing free black civil disabilities in line with Jamaica,73 and he wrote to Arthur agreeing that he needed some power to banish malefactors “foreign or British, whose conduct may be dangerous to the tranquillity and security of the Settlement” given that the King has “no power of establishing adequate Tribunals.”74 Banishment of foreigners was a popular solution everywhere in the Age of Revolutions.75 While British subjects could not be legally banished from most British territories,76 such limitations likely did not apply in Belize.

32The problem of jurisdiction came to a head in early 1815 when a group of 15 men including some Miskitu, Spaniards and Britons banded together in a ‘piratical’ attack on a party that included a Spanish Commissioner. He was robbed and his servant killed. The magistrates of Belize quickly issued a Warrant for their arrest. It claimed that “a Spaniard name Victorianna Barenta, with aid of James Neal, Benjm Lee, Benjn Myvett, John Goff, John Levill, Quecamena, Bob and Robinson, Negroes, and Charley and Raffreen Spaniards, and two Mosquito men and two little boys…” attacked a boat, murdered a crew member, and stole casks and other things “against the peace of our Sovereign Lord the king.”77 The band of pirates was captured immediately. As the band had clearly capital crimes, the issue of sovereignty arose in its most pointed form: did the settler magistrates have jurisdiction enough to try people for their lives when the settlement could not properly be said to be within the king’s peace? The power to kill legitimately lay at the heart of sovereignty, after all.

33The magistrates thought not. So Arthur waxed creative. In deference to the treaty, Arthur hastened to ensure that nothing whatever was done to the Spaniards or the Miskitu, even though the crime was committed within the agreed boundaries of the British settlement. He expected the Captain-Generalto respond with alacrity to punish the Spaniards, as his own Commandant had been robbed. Arthur was less sanguine about the Miskitu Men. Although the settlers from the southern side of the Bay had signed a number of treaties with the tribe in which the Miskitu declared themselves to be under the protection of the King of England, no one asserted that they should be tried in settler courts. First, their territory lay outside the region allowed to the loggers in the 1786 treaty. Second, whatever the treaties said, Miskitu Indians had no intention of submitting to any king. Some mixed-race children chose to live in the settlement as British loggers, including a man named Usher who petitioned home to be allowed to serve as a juror and magistrate.78 Others were enslaved – and became the object of enormous controversy later in Arthur’s tenure.79 Most, however, were Britain’s long-time allies and neighbours. As such, Arthur worried that the Miskitu king’s “deadly hatred towards the Spaniards,” would probably lead to the reward rather than their punishment of the Miskitu malefactors.80

34Arthur’s primary concern, then, was how to try the British Subjects involved in the band for theft and murder committed within the boundaries of the settlement. Feeling “unauthorized to proceed against the Offenders in their Court,” and in a marked departure from their stance in 1810, the magistrates met with Arthur and urged him “in council” to declare a state of martial law to try only the British perpetrators “before a Military Tribunal”.81 Far from disapproving of this use of martial law, Bathurst wrote in July to convey the Prince Regent’s “entire approbation of the measures” he had taken. This was so not least, because, by restoring the peace, Arthur facilitated inaction by the central government: his actions would “prevent the necessity of adopting any hasty measure for the future Regulation of the Settlement” as the government considered “whether the Evils to which the Settlement is from its anomalous state perpetually subject are capable of being remedied either by Legislative Enactments from hence or by Negotiation with the Spanish Government.” Bathurst dared not hold out any hope that anything good would come from the latter.82

35The Judge Advocate General had other ideas, however. A few months later, he sent Bathurst a terse note acknowledging receipt of the court martial proceedings from Belize. He noted that, “As the court appears not to have been constituted under the Mutiny Act, & the Individuals tried are not liable to any Jurisdiction sitting by its authority, the Judge Advocate General considers that these cases do not come within his Department.”83 In its contemporary form, the Mutiny Act gave Arthur no power to try or execute the civilians. Bathurst wrote a quieter letter to Arthur after receiving this advice. He said that he still approved of Arthur’s proceedings, not because they were legal, but because “the impossibility of obtaining the ends of Justice by a Trial before the Ordinary courts established in the Settlement appear to His Majesty’s government to afford sufficient grounds for having had recourse to a Court Martial.”84 In the absence of jurisdiction, Arthur’s actions were excusable through necessity. However, in law, Bathurst had to admit that the absence of sovereignty meant that foreigners could get away with murder in the settlement, and that no British subject could legally be tried for their life.85

Disciplining Subjects

36This left Arthur in a pickle. When, just a few months later, the slave Linda was accused of killing her child Flora in early 1816, given the inapplicability of the Mutiny Act, he felt pressed “most earnestly, to entreat your Lordship’s commands how Murderers are to be proceeded against in this Settlement for the future.”86

37Bathurst was already on the job, seeking a series of legal opinions about how, exactly, Arthur was supposed to keep the peace in Belize. He sent a very hopeful query to the King’s Advocate, Christopher Robinson, asking if Belize could not be treated like the high seas, and fall, therefore under Admiralty jurisdiction. Robinson said no: clearly Belize was land, not sea.87 By July the problem of Flora’s murder had ended up on the Law Officers’ desk. They stated that “The self-created courts… not having been established or confirmed by his Majesty, nor by the British Parliament cannot have legal jurisdiction to try offenders, and of course no sentence passed by them can legally be carried into execution.” The Treaties of 1763, 1783 and 1786 meant that settlers were merely private individuals living “by permission, in the Territory of a foreign State.” Accordingly, the King could not, “by virtue of his prerogative have the same right to erect Courts…. Or to make laws for their Government” as he might in other colonies. Parliament might do so, but only at risk of breaching the treaties. It might be possible to try offences in Belize before Spanish Courts – a measure that “might be attended with great evil both in a legal and political point of view.” The only alternative was to bring British subjects to England to be tried under 33 Henry c. 23,” a very old act asserting English jurisdiction over murders by British subjects abroad. However, foreign malefactors could not tried at all under that legislation.88 To add insult to injury, the law officers followed up in August with the opinion that Belize was also open to slave traders. Though slaves transported to the settlement on British ships could be condemned in Jamaica under the 1807 Abolition Act, British slave traders committing offences against the act in the settlement could not. Foreign ships could not be seized or condemned at all.89 The absence of sovereignty thus made the settlement a haven for the slave trade.

38When Downing Street timidly suggested that Arthur send British capital offenders to England for trial, Arthur replied that this was not practicable. In early 1817, he noted the enormous risk to order in the settlement: the “inability of the “Bench to proceed against… serious” offences cannot “be kept long a secret from the lower orders of this extensive community.” He begged, at least for “Powers to act in cases of emergency.”90 So the cycle started again. A marginal note on this letter asked for legal opinion as to whether local trial could be held by “extending military law, by His Majesty’s Proclamation, or some legislative provision.”91 As it happened “some legislative provision” was eventually made. In 1817 Parliament commissioned colonial admiralty courts in “any of His Majesty’s Islands, Plantations, Colonies, Dominions, Forts or Factories” to try murder or manslaughter cases brought against Britons “on Land” in the Pacific Islands and Honduras.92 This was a ridiculous solution for the Pacific Islands, as the closest admiralty court was at Sydney. However, it should have been a feasible solution in Honduras because the nearest admiralty court was not so far away in Jamaica. More work needs to be done to determine how many cases were tried under this provision.

39We know it was not many because two years later Parliament passed another act to facilitate the “more effectual Punishment of Trial of Murders, Manslaughters, Rapes, Robberies and Burglaries… in Honduras” (59 Geo. 3 Cap XLIV). This act allowed the King to issue commissions to “Four or more discreet Persons, as the Lord Chancellor of Great Britain… shall… think fit to appoint” to hear all such crimes committed on land in the Belize settlement. Thereafter, seven judges were appointed (without pay), “any three” of whom could constitute a criminal commission. The judges appointed one among them to be Judge Advocate, and the Superintendent acted as president with powers of sentence and reprieve. The commission operated with a jury and seems to have applied a combination of English law and the Barnaby Code. Lower ‘courts’ (including a slave court) continued to operate on the basis of custom and consent.93 Here parliament parlayed its obligations under the treaty by creating a court under the guise of an ad hoc commission with extraterritorial jurisdiction over subjects on foreign soil. But their delicacy was a ruse: everyone called the commission a Supreme Court. In contradistinction to the extraterritorial regimes constructed in the Mediterranean and China on the basis of treaties, and in a move Parliament repeated much later when it empowered Naval Officers to seize slave ships in Portuguese and Brazilian waters, this act indemnified judges for exercising jurisdiction in defiance of its treaty obligations.94

40If the jurisdictional issue was resolved in practice, the problem of sovereignty and jurisdiction remained. Commissioners of Inquiry sent to Belize to inquire into its state in 1824 noted in a private report that the superintendent himself “did not know what his powers were” to “banish, imprison and fine or otherwise punish” the inhabitants.95 This is not surprising given that, just two years earlier, Bathurst had warned Arthur to “bear in mind and strongly to impress upon your successor that the Authority of a Superintendent upon Shore is of so doubtful a nature in point of law that it may be considered rather as Conventional than strictly legal,” (that is, the Superintendent’s authority rested on local tolerance and custom rather than law).96 They also worried about the legislative foundations of the capital jurisdiction exercised by the so-called Supreme Court. In this new era of accountability, they felt, it “has now become a matter of utmost urgency… to put this question at rest by the competent Authority; and to prevent the continuance in the exercise of the highest powers of the sovereign, by his subjects, without any special delegation on his part” and without “even establishing as a preliminary principle, who is to be considered the Sovereign competent to delegate such authority.”97

41Not so long before, James Stephen Jnr, now the permanent legal counsel to the Colonial Office, had expressed similar concerns. But by the time he read the Commissioners’ reports he had had enough. He told undersecretary Horace Twiss that “If we are ever to establish legal Tribunals at Honduras it must be upon the same principle as at the Swan River – that is, we must authorize the local authorities to do what is needful. Half a dozen lines are all for which we need to resort to Parliament. I presume however that the subject may be allowed to slumber for another year at least.”98 Sovereignty, in this much more modern rendering, was necessity, and it need not be territorial at all.

Conclusion

42There are very few margins of the British Empire where the nature of sovereignty and subjecthood were more explicitly and constantly discussed (and more inconsistently understood) than in the settlements that became British Honduras. There, sovereignty was defined and redefined in its absence as treaty provisions preserving Spanish sovereignty transformed problems of local disorder into problems of international law. In the process of trying to keep faith with Spain, while struggling to keep the peace, settlers, lawyers, colonial administrators and London bureaucrats stumbled repeatedly over the muddy notion of sovereignty in empire. Keeping the peace in Belize produced some of the most confusing discussions of the interrelation of sovereign, territory and jurisdiction in the early nineteenth-century public record – decades before such questions were resolved in colonies like New South Wales.99

43James Marriott thought the very fact that Spain tolerated the settlement in the Treaty of Paris of 1763 carried territorial rights enough to establish a superintendency, and possibly a court: a shadow of sovereignty that could overlay Spanish claims to land. Sovereignty according to the Convention of 1786 forbade British settlers from the tilling of soil, let alone the establishment of any sort of government, though some concessions could be made to keep the local peace. However, the relationship of sovereignty and even this lightest form of government was tested repeatedly in clashes between settlers and superintendents, the former vacillating between claiming jurisdiction by custom or refusing to act at all. For their part, superintendents challenged settler claims to jurisdiction and experimented with martial law. All begged the Colonial Office for a solution that would allow them to keep the peace lawfully. The problem of exercising jurisdiction without territorial sovereignty emerged repeatedly in early nineteenth-century Belize, precipitating overlapping crises of legitimacy and order in the colony. These crises were papered over, but not resolved, by legislation that reasserted the power of the king over British subjects, wherever they might live. So it was that sovereignty itself was defined and redefined at the juncture of local order and the law of nations in a tiny settlement in the swampy forests of Belize.

Bibliography

BELMESSOUS, SALIHA (ed), Native Claims: Indigenous Law against Empire, 1500-1920,(Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

BENTON, LAUREN, A Search for Sovereignty: Law and Geography in European Empires, 1400-1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

BENTON, LARUEN, Law and Colonial Cultures: Legal Regimes in World History, 1400-1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

BENTON, LAUREN, “Possessing Empire: Iberian Claims and Interpolity Law,” in ed. Saliha Belmessous, Native Claims: Indigenous Law against Empire, 1500-1920,(Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 19-40.

BENTON, LAUREN and BENJAMIN STRAUMAN, “Acquiring Empire by Law: From Roman Doctrine to Early Modern European Practice,” Law and History Review 28.1 (2010), 29-37.

BENTON, LAUREN, and LISA FORD, Rage for Order: The British Empire and the Origins of International Law (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2016),

BOLLAND, O. NIGEL, The Formation of a Colonial Society: Belize, from Conquest to Crown (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977).

BOLLAND, O. NIGEL, “Reply to William A. Green’s ‘The Perils of Comparative History,’” Comparative Studies in Society and History 26.1 (1984), 120-125.

BOTELLA-ORDINAS, “Debating Empires, Inventing Empires: British Territorial Claims Against the Spaniards in America, 1670-1714,” Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 10.1 (2010): 142-168.

Dobson, Narda,A History of Belize (London: Longman Caribbean, 1973).

ELLIOT, JOHN, Empires of the Atlantic world: Britain and Spain in America, 1492-1830 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2006).

FITZMAURICE, ANDREW, King Leopold’s Ghostwriter: The Creation of Persons and States in the Nineteenth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021).

Floyd, Troy S.,The Anglo-Spanish Struggle for Mosquitia (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1970).

FORD, LISA, Settler Sovereignty: Jurisdiction and Indigenous People in America and Australia, 1788-1836 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010).

GARDNER SORSBY, VICTORIA, “British Trade with Spanish America under the Asiento, 1713-1740,” (Unpublished Ph.D., University of London, 1969).

GREEN, L.C. ‘Claims to Territory in Colonial America,’ in L.C. Green and Olive P. Dickason, The Law of Nations in the New World (Edmonton, Alberta: University of Alberta Press, 1993).

GREEN, L.C., OLIVE P. DICKASON, The Law of Nations in the New World (Edmonton, Alberta: University of Alberta Press, 1993).

HUMPHREYS, R.A. The Diplomatic History of British Honduras, 1638-1902 (London: Oxford University Press, 1961).

JANSEN, JAN C., “Aliens in a Revolutionary World: Refugees, Migration Control and Subjecthood in the British Atlantic, 1790s-1820s,” Past & Present (2021, online): https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtab022.

JOSEPH, GILBERT M., “British Loggers and Spanish Governors: The Logwood Trade and Its Settlements in the Yucatan: Part 1,” Caribbean Studies 14 (1974), 7-37.

JOSEPH, GILBERT M, “British Loggers and Spanish Governors: The Logwood Trade and Its Settlements in the Yucatan: Part 1,” Caribbean Studies 15 (1975), 43-52.

LESTER, ALAN, FAE DUSSART, Colonization and the Origins of Humanitarian Governance (Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, 2014).

McKENZIE, KIRSTEN, “The Laws of his Own Country': Defamation, Banishment and the Problem of Legal Pluralism in the 1820s Cape Colony,” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 43(5) (2015), 787-806.

MULICH, JEPPE, In a Sea of Empires: Networks and Crossings in the Revolutionary Caribbean (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020).

PAGDEN, ANTHONY, “Law, Colonization, Legitimation, and the European Background,” in The Cambridge History of Law in America, Vol. I, Early America (1580–1815), ed. Michael Grossberg and Christopher Tomlins (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 1–31.

PAGDEN, ANTHONY, Lords of All the World: Ideologies of Empire in Spain, Britain and France, c.1500–c.1800 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1995)

SHMILOVITS, LIRON, “Deus ex Machina: Legal Fictions in Private Law,” (Unpublished PhD, Cambrdige, 2018).

Sorsby, William Shuman, “The British Superintendency of the Mosquito Shore, 1749-1787,” (Unpublished Ph.D., University of London, 1969).

TEMPERLEY, HAROLD W.V. “The Causes of the War of Jenkins’ Ear, 1739,” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 3 (1909), 197-236.

TROY, NICHOLAS, “‘Right of Dominion’?: A Comparative Analysis of Legal Doctrine in the Colonial Claim-making of British Settlements in the Spanish Peripheries of Darien, the Mosquito Coast, and the Yucatán Peninsula, c.1630 – c.1790,” 29 June 2021, Scottish Centre for Global History, https://globalhistory.org.uk/2021/06/right-of-dominion/.

TULLY, JAMES, An Approach to Political Philosophy: Locke in Contexts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

VAN HULLE, INGE, Britain and International Law in West Africa: The Practice of Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

VAN ITTERSUM, Martine J., Profit and Principle. Hugo Grotius, Natural Rights Theories and the Rise of Dutch Power in the East Indies (Leiden, Brill, 2006)

WOODFINE, PHILILP, Britannia's Flories: The Walpole Ministry and the 1739 War with Spain (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Royal Historical Society, 1998).